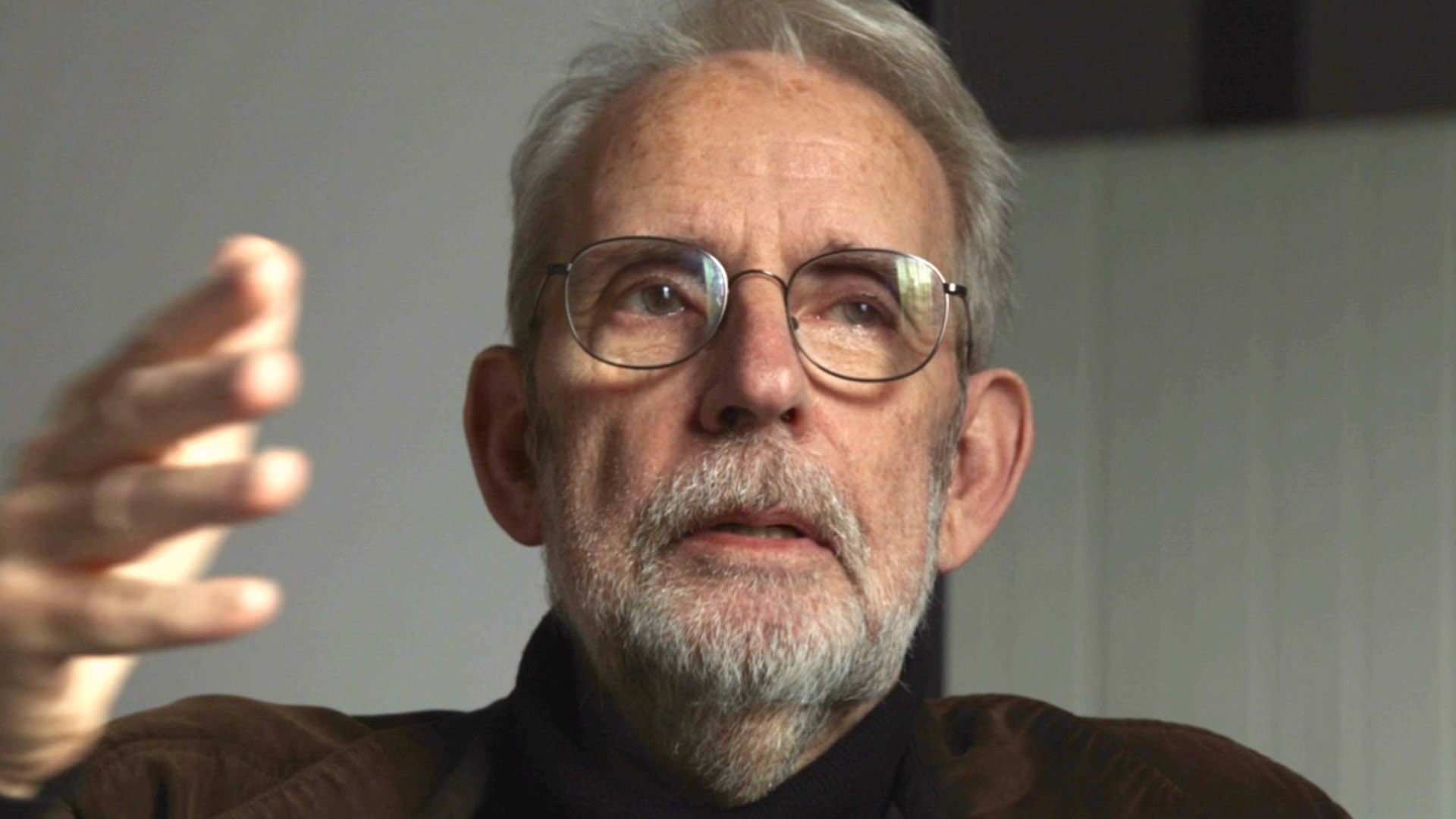

“Music as Mist”: Sound Designer Walter Murch Looks Back on American Graffiti, 50 Years Later

Murch collaborated with George Lucas to create an innovative soundscape using classic rock-n-roll recordings.

Near the end of post-production on Lucasfilm’s American Graffiti (1973), director George Lucas and sound mixer Walter Murch (his official screen credit would be “Sound Montage and Re-recording”) were busy making last adjustments to the movie’s soundtrack. “It was two o’clock in the morning, not quite an all-nighter, but close to it in order to meet the deadline,” Murch tells Lucasfilm.com. “At that same time, I was editing The Conversation [released in 1974, and directed by Francis Ford Coppola]. During the day, I’d work on The Conversation, and at night I’d be re-mixing American Graffiti.

“We were going through the film,” Murch continues, “working on Reel Two, and I asked the machine room operator, who had to jockey all of the reels of film, ‘Can you get R2-D2?’, meaning ‘Reel Two Dialogue Two.’ And George, who was asleep in a cardboard box behind me, suddenly woke up and said, ‘What did you say?’ I replied, ‘I didn’t say anything, go back to sleep.’ But he said, ‘No, no, you said something.’ I explained, ‘I asked for R2-D2’ and George said ‘What a great name!’ I had no idea what he meant, but that was it.”

As they finished Graffiti, Lucas had been making notes for his next project, a space fantasy ultimately called Star Wars. That late night request from Murch would be the inspiration for one of the Star Wars saga’s central characters. But it was the completion and resulting success of American Graffiti that made Star Wars possible in the first place. And the cinematic achievement of the film was due in part to the innovative contributions of Walter Murch.

A contemporary of George Lucas, Murch grew up in New York City, and was unfamiliar with the teenage car culture that so inspired the Californian who would become his friend and collaborator. “Our family didn’t have a television or even a car until the late ‘50s,” Murch explains. “There was a lot of public transportation. I must’ve been about 14, and a senior at our high school had graduated, and he drove up in a red MG sports car. It exploded my mind that a student could actually drive a car. This idea that there’s a world out there, the fantasy Modesto world where kids don’t exist without their car [was new to me].”

Murch and Lucas first met as film students at the University of Southern California in 1965. Sharing a passion for cinema, they became fast friends in the bustling community of young filmmakers. “George made a student film called The Emperor, which was not about cruising, but it was about a disc jockey who had a psychic hold on the youth of Los Angeles,” Murch recalls. “So that sort of adjusted me to one theme that later inspired American Graffiti.”

Both Murch and Lucas were among the cohort that joined Francis Ford Coppola at the new American Zoetrope studio in San Francisco in 1969. Together, they co-wrote the screenplay of Lucas’ feature directorial debut, THX 1138 (1971), and Murch also worked as sound designer on the project (an emerging term and role which he helped define). Both young men approached the use of sound as a critical element of the filmmaking craft, something commonly overlooked by many directors and screenwriters. Together, they’d innovate new ways to use sound to help tell a film’s story.

American Graffiti’s story “was very challenging from a structural point of view,” as Murch explains, “because it tells the story of four people and they’re all intertwined. You see all of them together at the beginning, then it explodes and you follow each one of these guys over a single night. It’s a classic, what they call Aristotelian story. There’s a unity of time, though not unity of place or character. You’re following four, which is a big number. You can follow two or three, but to keep juggling four characters – who is this guy, what’s his problem, what’s he trying to achieve, and who’s this girl he’s with? – is a challenge. The screenplay went through a lot of permutations before it felt solid on that ground.”

Production on Graffiti stretched over six weeks in the summer of 1972. Murch made a few visits to the set before his own work began after the filming’s completion (he also served as the location sound recordist for a few re-shoots, including the scene when Curt [Richard Dreyfuss] receives a fateful call from a payphone). Editing on Graffiti took place in the quiet town of Mill Valley, north of San Francisco, at a home owned by Francis Ford Coppola, one of the film’s producers.

“The work on American Graffiti was done over the garage of this house,” Murch explains. “We never went into the house itself, but there was a sort of guest house with two rooms over the garage where all of the editing took place. [Picture editors] Marcia Lucas and Verna Fields and George were kind of higgledy-piggledy in those rooms. My work as the sound designer and editor started pretty much after all of the picture editing had been done.” Murch notes that “the first assembly of the cut was three hours, which was too long for the kind of film it was. There was a desperate struggle, because when it was cut down to close to two hours, that structure broke apart. So then there was another struggle to get into its final shape.”

Almost a character in the story itself, music was essential to Graffiti. George Lucas had developed the screenplay with specific rock-n-roll songs assigned to each scene. Those songs would be presented as entries in an all-night radio program hosted by Wolfman Jack (a real-life disc jockey who played himself in the film). One of Murch’s key tasks was to integrate this broadcast throughout the film, and he and Lucas found a way to do so that made it sound distinctly realistic, as if the music was coming directly from the speakers inside the cars visible onscreen.

“Marcia Lucas cut together the entire one-hour-and-fifty-minute program with all of the commercials, music, and Wolfman Jack stuff,” Murch explains. “We had that on one Nagra recorder playing through a speaker. That was George’s responsibility. Then I was as far away from him as I could get in the yard of this house in Mill Valley, with another Nagra and a microphone. We went through all two hours of this program. George would slowly move the speaker from one side to the other, and I would correspondingly move the microphone. Sometimes they were pointed in opposite directions; sometimes they were pointed right at each other. This gave you a floating sense of reverberation. We did that for two hours, and then we did it all again, knowing we’d never match it up.

“In the final mix, I had three tracks: the original radio program as clear as it could be, and these two atmospheric tracks,” Murch continues. “Depending on the scene, I could shift into high-reverb or I could put the music up front. It’s the acoustic equivalent of depth of field in photography. When you shoot a portrait of somebody, you want the background to be out of focus. This was a way to have the music be out of focus in the background when there was a dialogue scene in the foreground. The dialogue was as crisp and clear as you could make it, and the music was this shimmering veil in the background that you knew was music, and you could kind of follow it, but it wasn’t distracting you from the dialogue.”

Nearly every scene in the film utilized this technique, which Murch dubbed “worldizing.” One especially poignant example comes in the middle of the story, when Curt yet again sees a white Thunderbird driven by an alluring woman whom he is desperate to meet. As he chases the car on foot down the street, “Barbara Ann” by The Regents echoes from passing cars, constantly shifting in pitch, volume, and sharpness. “It was a bit of free-form mixing,” Murch notes. “The goal was to have these big shifts from music as mist, where it’s kind of vague, and then a car would suddenly appear and it’s in your face. As it goes by, it would disappear again. It plays on the disorientation of Curt in that moment, because he’d seen her again.”

For the memorable freshman sock hop scene at the local high school, Murch took his microphone and recorder to the same gymnasium where the sequence had been filmed (Mill Valley’s Tamalpais High School) with the band Flash Cadillac and the Continental Kids. “We ‘gym-ized’ it,” he says. “We played the music through a speaker and recorded it from the other side of the gymnasium. When I mixed that in the final version, I had three tracks to use: the dry studio recording and two ‘gym-ized’ versions. One was slightly out sync, so it gives you that feeling that you’re live with the band. The original mix of Graffiti was in mono, so you didn’t have any spatial cues in the theater. But doing this gave you a sense of space, as much as you can get in a monophonic recording.” (Murch also adds that he’d first developed this technique for the opening wedding sequence of 1972’s The Godfather.)

These subtle but meaningful approaches to film sound helped influence a sea change in filmmaking as a whole, one that fueled the growth and success of Lucasfilm’s own Skywalker Sound in later years. Graffiti’s use of a non-original soundtrack (something unusual for the time) to help convey its story was similar to a “Greek chorus,” as Murch puts it, “in the sense that they comment on the action of the story. We didn’t spike any single words in a song, but we hoped that the song itself would convey that sense. The songs were all very familiar with audiences at that time. Much of the audience had grown up with those songs, just like the characters in the film. So they immediately would plug into the meaning of the music.”

It was a new way of doing things, and not everyone was onboard at first. Murch recalls a conversation where “Verna Fields – who was subsequently the editor of Jaws – took me aside and said, ‘Walter, you have to convince George to get rid of all this music because it’s ruining a wonderful film about these wonderful characters. People are going to go crazy and want you to turn off this music.’ I told her, ‘I know what you’re talking about, Verna. I know that effect, and we’re doing something that will forever solve this problem.’ She went away shaking her head, thinking that we were crazy. But it worked.”

Graffiti’s distributor, Universal Studios, was also skeptical, in part because the film’s music licensing required an exorbitant cost. “George wanted to get Elvis in there, of course, but it was just too expensive,” Murch explains. “Those 42 songs cost $80,000. That’s some $2,000 a piece for the performance and copyright. Universal thought that was outrageously expensive. They wanted George to record sound-alikes with a band that they knew. George said, ‘No way.’” In the end, Graffiti’s soundtrack record from MCA became a top-seller in its own right, even spawning a number of spin-off records with more classic hits.

After his success on Graffiti, Murch continued his groundbreaking work in both sound and picture editing, something he still does to this day. He’s also continued to revisit Lucasfilm’s first production, overseeing the first stereophonic Dolby mix in 1978, and most recently, a new 5.1 digital mix that is premiering in August 2023 with Graffiti’s 4k restoration. Murch collaborated with Skywalker Sound’s Pete Horner on the latter project.

“It’s an innocent story, in the sense that it’s about American teenagers before John F. Kennedy was killed,” Murch reflects on the film. “They all have ideas about their future. Curt thinks he might become an assistant in the White House. But just a year after the story of the film, all of that changed.”

By providing George Lucas with the opportunity to make Star Wars, American Graffiti itself would forever change the career of George Lucas and the company he founded. For Murch, it all goes back to the seemingly inauspicious moment when he asked for “R2-D2.” It was only after the release of Star Wars: A New Hope (1977) when the sound designer happened upon the handwritten page where Lucas had scribbled “R2-D2, great name!” “I took that piece of paper, framed it, and gave it to George,” he says. “It could have easily been lost.”

Lucas O. Seastrom is a writer and historian at Lucasfilm.

—

Lucasfilm | Timeless stories. Innovative storytelling.