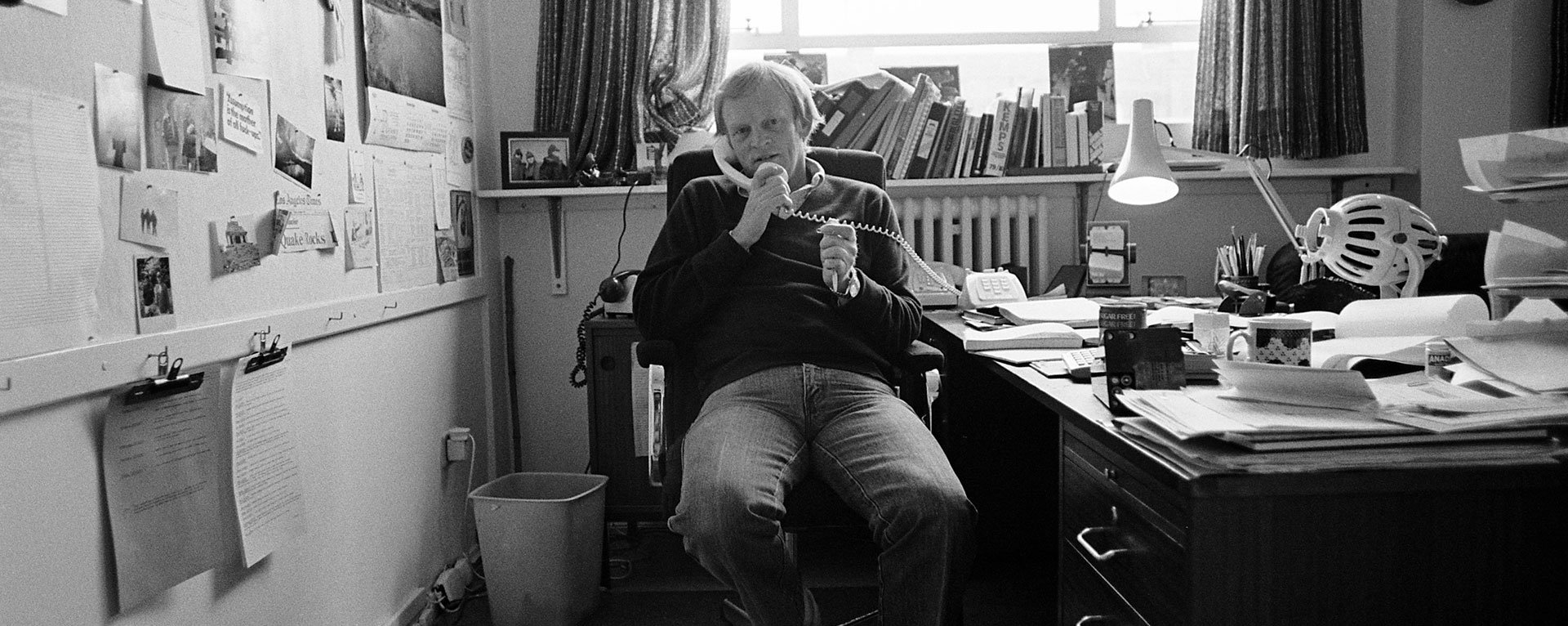

Robert Watts: 1938-2024

The producer was an essential member of the crew that made the first Star Wars and Indiana Jones trilogies.

Lucasfilm is deeply saddened to learn of the passing of Robert Watts at the age of 86. The producer was intimately involved in the making of half a dozen Lucasfilm classics from 1977’s Star Wars: A New Hope to 1989’s Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade.

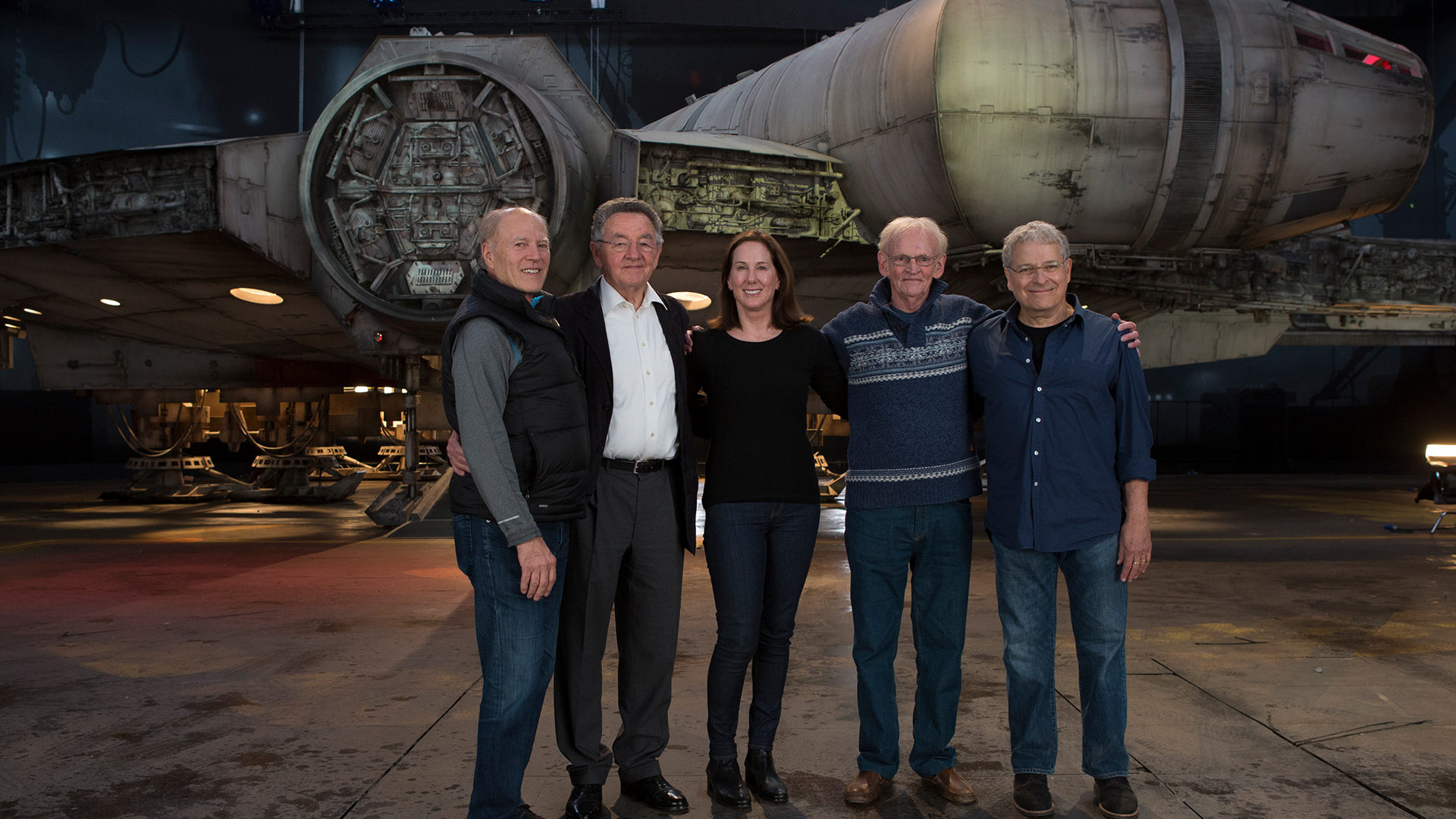

“It’s not an overstatement to say that, without Robert Watts’ involvement, Lucasfilm would be a very different company today,” says Kathleen Kennedy. “Not only did he bring his own skills to the production of several milestone films, but also gave opportunities to so many other important crew members to do so as well.”

Watts was born in London in 1938, the grandson of a screenwriter at the historic Ealing Studios, where the young Watts was first hired as an assistant office boy in 1960 at the age of 22. “I reckon I was about ten years old when I first went on a film set,” he would recall, “and it was about that age that I decided it was the life for me.”

Watts had studied at Marlborough College in England and Grenoble University in France before serving as an officer in the Royal West African Frontier Force in Nigeria. Years later, while working as co-producer of Star Wars: Return of the Jedi (1983), he took a small cameo role as an Imperial officer alongside director Richard Marquand. “It turned out that the character was called ‘Lieutenant,’ which was in fact my rank in the English army,” Watts explained.

Throughout the 1960s, Watts climbed the production ranks of the British film industry, from second assistant director on movies like Thunderball (1965) to production manager on 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). While working on location in Mexico for The Wrath of God (1972), he was contacted by producer Gary Kurtz, then working with George Lucas on American Graffiti (1973). Three years later, Kurtz remembered the capable Englishman, and Watts joined the Star Wars: A New Hope team as production supervisor.

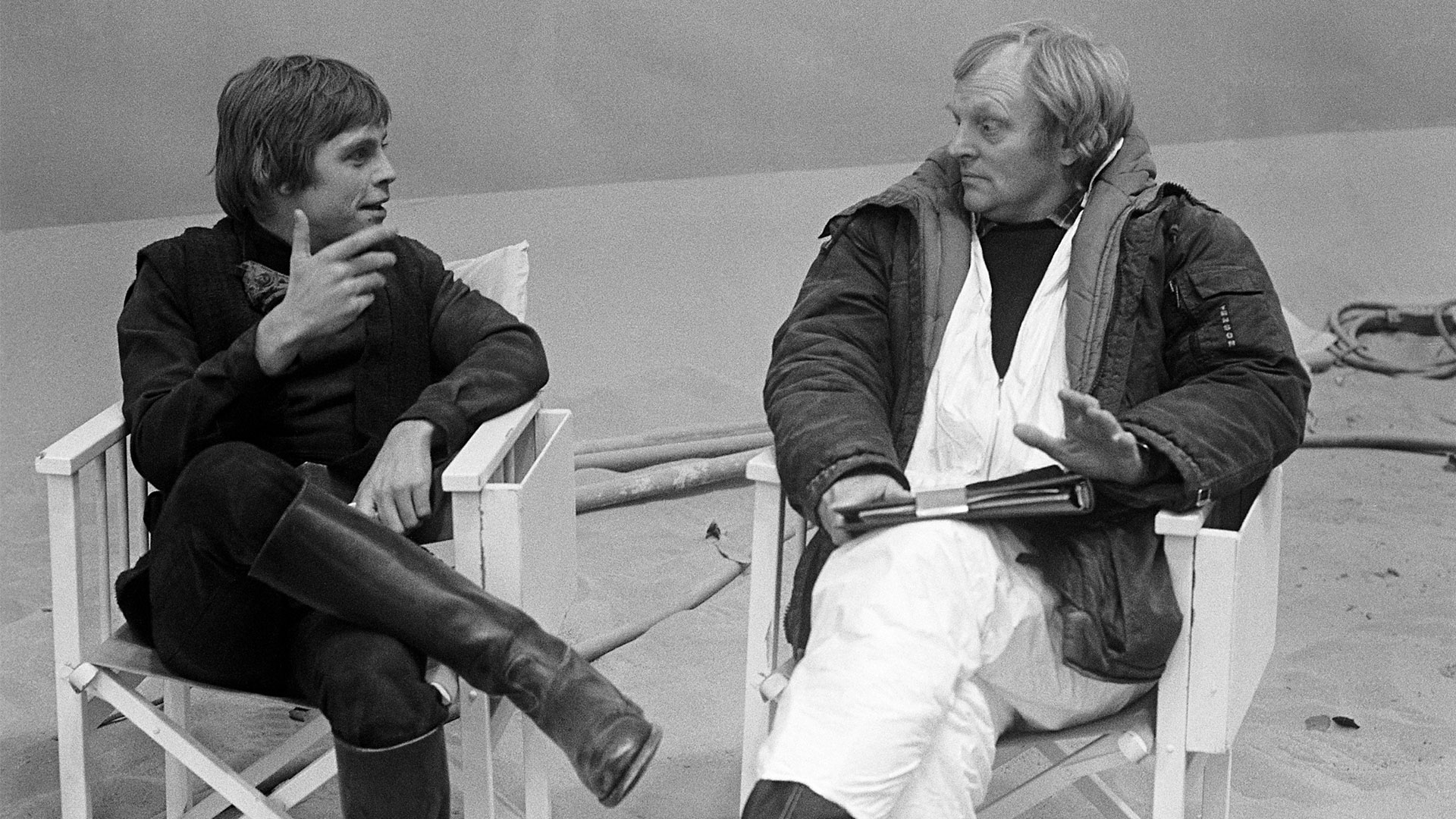

“Sometimes you can work with a director and really think you’re getting a lousy picture, and that’s depressing,” Watts said during work on the first Star Wars feature. “But that’s not the case here at all. I think that if we can make as good a picture as American Graffiti, then I think we’re in.” When the film was finally released to phenomenal success, Watts found himself on location for another movie in Afghanistan. He managed to pick up a copy of Time magazine to find pictures of Star Wars. “I thought, Bloody hell!” he’d say. “ I had no idea it had taken off to such a huge extent.”

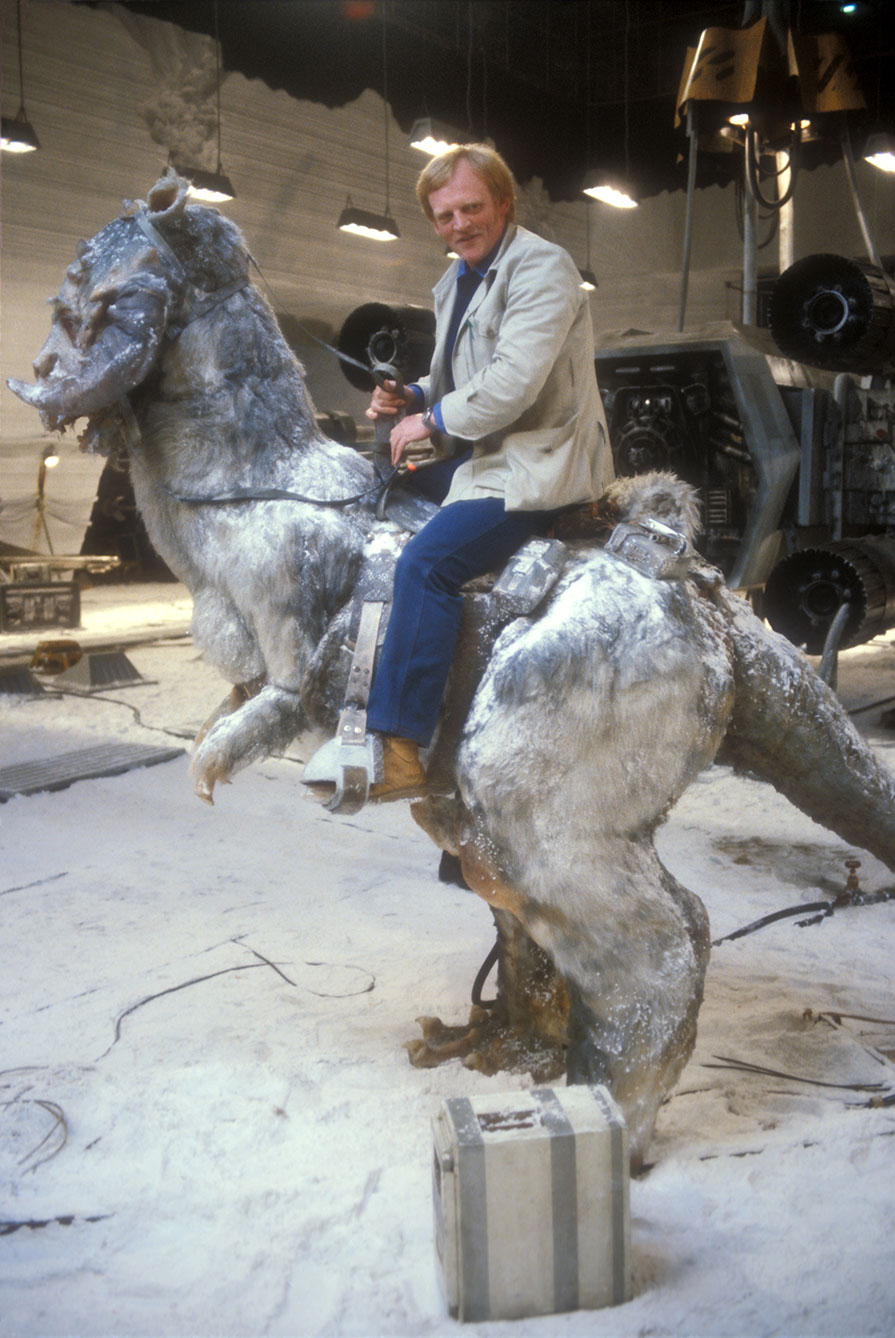

Throughout his tenure with Lucasfilm, Watts was responsible for organizing each production’s crew members in England, as well as assisting with local casting. Along with production designer Norman Reynolds, he was also Lucasfilm’s chief location scout, leading “recces,” as they’re known in the United Kingdom, from the northern Saharan desert of Tunisia to the snowy landscapes of Norway, and from the island of Sri Lanka in the Indian Ocean to the mountain ranges and coastal forests of the western United States. “A film location must offer two essentials,” Watts explained. “Accommodation for the crew and a link with transportation to get people and equipment in and out. Otherwise, filming at the North Pole would be feasible.”

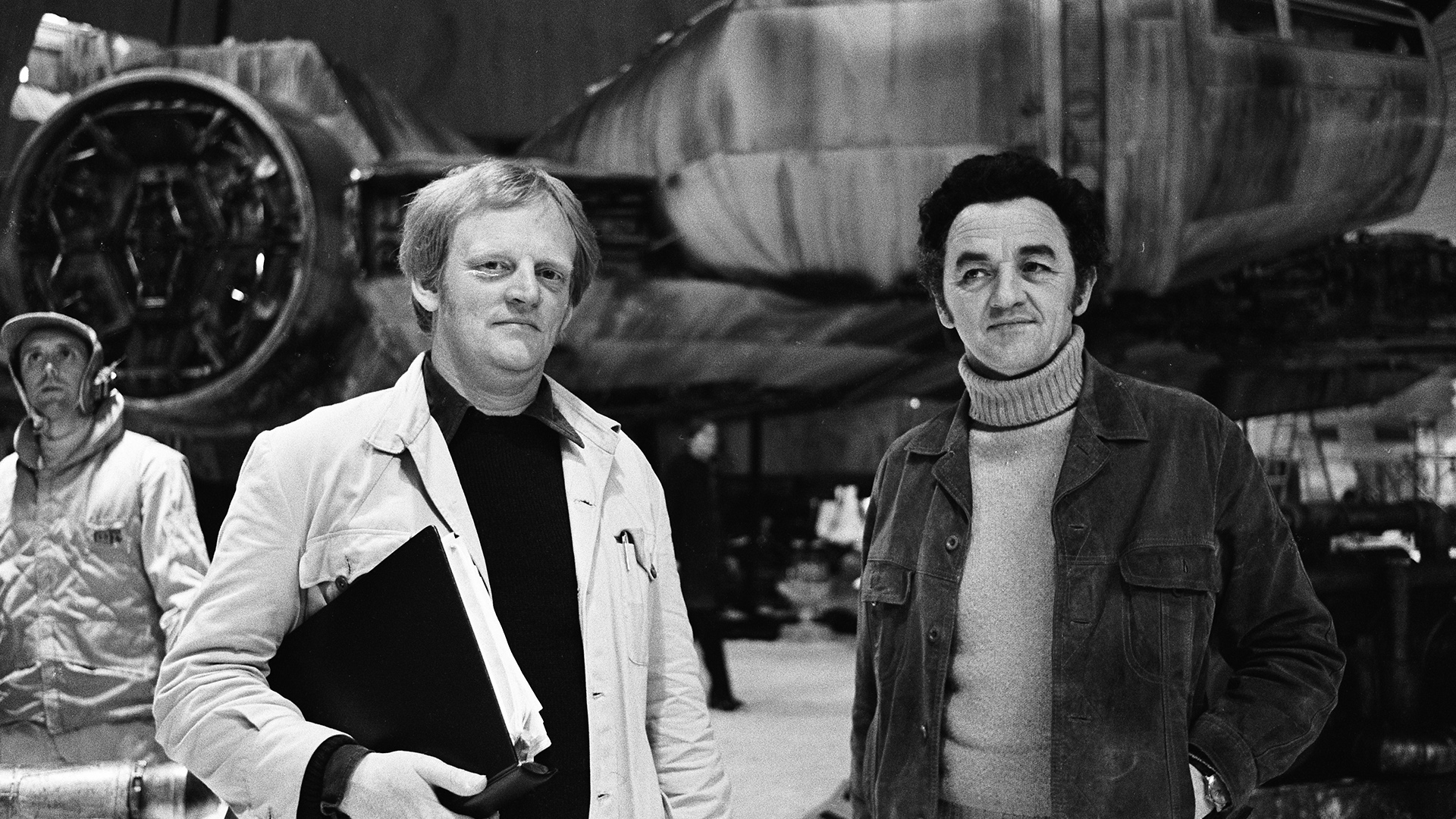

Watts was often the man on the ground, managing day-to-day logistics and operations, solving dozens of small problems every week. In the case of Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back (1980), the future of Lucasfilm was quite literally on the line. As the film faced one insurmountable challenge after another, Watts was among the key decision makers who determined how to complete the shoot as quickly and efficiently as possible.

“Robert Watts was a wonderful, wonderful man,” director Irvin Kershner said during Empire’s production. “Whenever he had a problem he came to me. He knew what he was doing and we had a lot of problems and he just sat there quietly and solved them. I loved him.”

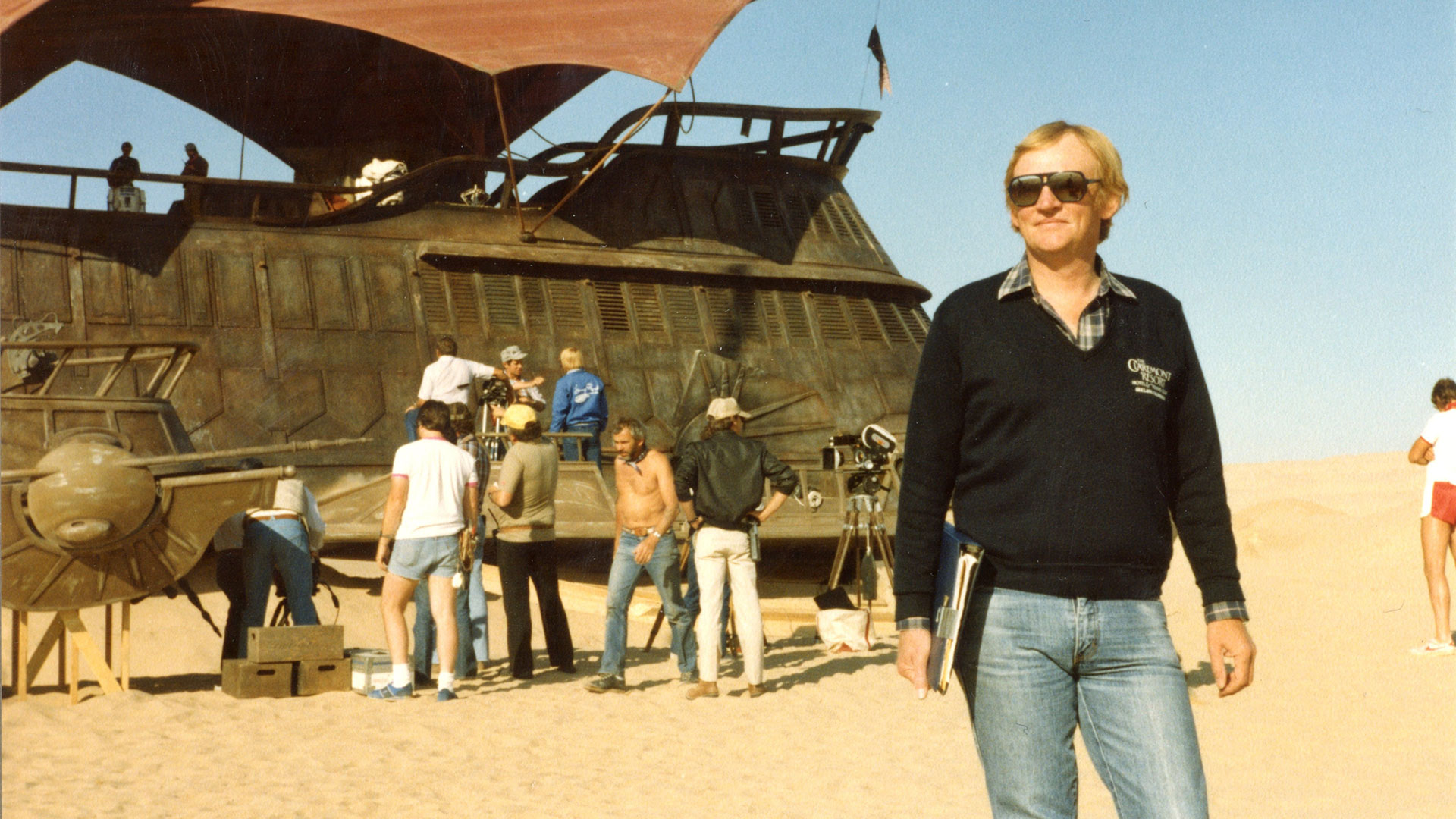

Before one film was released, Watts was typically already on the way to making the next one. While shooting Raiders of the Lost Ark at Elstree Studios near London, Watts fell suddenly ill with appendicitis. Though he likely felt the episode was best forgotten, he was surprised – and likely flattered – when two years later a fan yelled from the fence surrounding Star Wars: Return of the Jedi’s giant sail barge set: “Hey Robert, how’s your appendix?” If Watts was not aware of his growing celebrity within the Star Wars and Indiana Jones communities, that moment likely cemented it for him.

Watts was also instrumental in granting opportunities to those close or known to him, like his half-sibling Jeremy Bulloch, who would be cast as the unforgettable Boba Fett in The Empire Strikes Back. “I’d never managed to give Jeremy a job on a film,” recalled Watts. “So I rang him up and said, ‘If the suit fits, the part’s yours.’”

Watts’ next door neighbor Julian Glover, who had previously played a minor part in Empire as General Veers, credited the producer for landing him the role of Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade’s chief villain, Walter Donovan. “It was one of the happiest experiences in my life,” recalled Glover. “Then Robert Watts suggested that my wife in real life play my onscreen wife, and she was delighted to do it.”

Even as his active work with Lucasfilm came to an end, Watts managed to make a significant impact on the company’s ongoing history. Producer Rick McCallum had become friends with Watts while making the film Dreamchild (1985) at Elstree Studios. One day, Watts was touring George Lucas through the facility, and introduced the two Americans, thus sparking another creative partnership that spanned more than 20 years of film and television at Lucasfilm, including the Star Wars prequel trilogy.

“I have gained enormous experience because Lucasfilm has been innovative,” Watts explained in the 1980s. “It has been an enormous experience to work with George and to have worked with Steven Spielberg. I entered as a production manager and leave as a producer. That’s quite different. That gives me, by association, a credibility as I re-enter the freelance world. But one thing I have to re-learn is that all my future films are not going to enter the top ten. I’ve worked on many movies that didn’t make their advertising cost back, let alone the cost of the movie, so it’s been great to work on movies that people actually see.”

Film is one of the ultimate collaborative artforms, and film artists can’t hope to tell stories without production staff at their side. It takes a village, and Robert Watts helped build it.

Lucasfilm | Timeless stories. Innovative storytelling.