Lucasfilm Celebrates 30 Years of Radioland Murders

George Lucas’ madcap mystery-comedy originated during Lucasfilm’s earliest years.

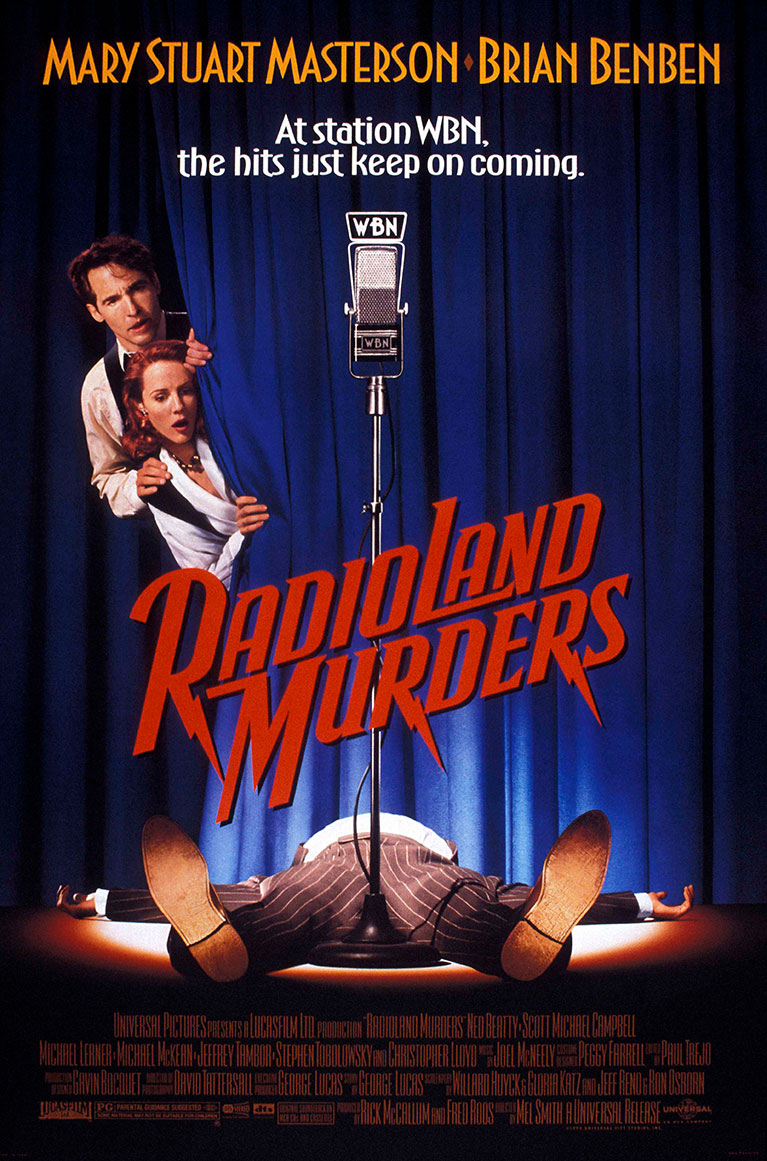

In October of 1994, Lucasfilm and Universal Pictures released the feature film Radioland Murders. A combination whodunit and screwball comedy originated by George Lucas, Radioland takes us back to 1939 at Chicago’s station WBN on its premiere night….

As the live studio audience pours in for the gala event, the situation backstage is anything but under control. Hectic, last-minute preparations are made for the coming broadcast while the program’s head writer, Roger (Brian Benben), is attempting to win back the love of his wife, studio secretary Penny (Mary Stuart Masterson), who has threatened to leave him. Penny’s attentions are elsewhere, however, as she is forced to take on the roles of director, producer, and stage manager in light of her colleagues’ spectacular ineptitude. Little does the sparring couple know that their feud will be the least of their troubles tonight.

By the time Radioland Murders reached movie theaters, executive producer George Lucas had spent 20 years working to get it made. In the wake of American Graffiti’s release in 1973 (another story that dealt with Lucas’ fascination with radio), Lucas was busy developing multiple stories for his upstart company, Lucasfilm. Among these was a space fantasy adventure that would become Star Wars: A New Hope (1977); a globetrotting adventure story about an archaeologist that became Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981); still another was a Vietnam war story, which George Lucas eventually gave to his friend Francis Ford Coppola as Apocalypse Now (1979).

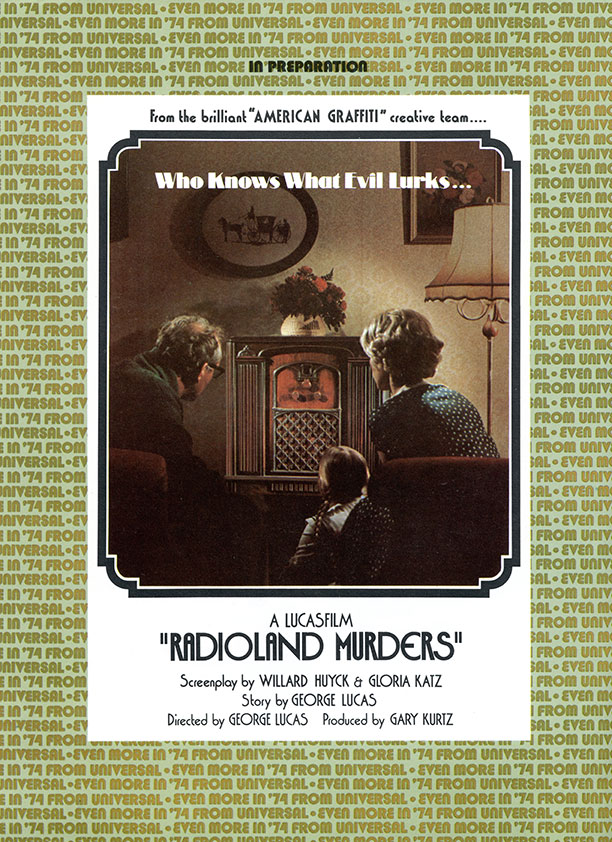

Radioland Murders was the last film in this early batch of projects. In 1974, Universal, who’d distributed American Graffiti, included Radioland in a catalog of its upcoming features. A photograph showed a family huddled around a vintage radio with the tagline, “Who knows what evil lurks…” (borrowed from the iconic, 1930s detective radio program, The Shadow).

At the same time that he was developing the screenplay for Star Wars, Lucas was also working on a script for Radioland with friends Gloria Katz and Willard Huyck. The married couple had co-written Graffiti with Lucas, and would eventually assist with the Star Wars script before writing Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (1984) and helming Lucasfilm’s Howard the Duck (1986). Huyck and Katz had delivered a first draft screenplay for Radioland by 1976, but by then, plans had changed.

Other projects took precedence for Lucasfilm, beginning with Star Wars: A New Hope. As time allowed, George Lucas continued to attempt to get Radioland off the ground. In the late 1970s, it was reported that comedian Steve Martin was being considered for Roger and Graffiti actress Cindy Williams (then popular as the co-star of TV’s Laverne and Shirley) was in the running for Penny. A dance number earmarked for the film even helped inspire the memorable opening of Temple of Doom, when Willie Scott (Kate Capshaw) leads a Busby Berkeley-esque musical rendition of “Anything Goes.”

By the early 1990s, Lucasfilm had established a new production unit busily criss-crossing the globe to make the award-winning TV series, The Adventures of Young Indiana Jones (1992-96). Producer Rick McCallum had recruited a top-notch group of creatives, from cinematographer David Tattersall to art director Gavin Bocquet to composer Joel McNeely. Lucasfilm, meanwhile, had continued to innovate digital tools like the SoundDroid and EditDroid (sold to Avid in 1993) in order to improve the craft of filmmaking. George Lucas knew he’d be returning to the Star Wars galaxy soon with a prequel trilogy of films; the all-important digital toolset needed continued development on a feature film scale; McCallum’s seasoned professionals needed another project when Young Indy had a lull in production; and that 20-year-old Radioland Murders script had still never been made. Perhaps now was the time.

With a commitment from Universal to distribute, screenwriters Jeff Reno and Ron Osborn revised Huyck and Katz’s earlier draft. McCallum was joined by fellow producer Fred Roos, who’d previously worked as casting director for American Graffiti. To lead the effort, Englishman Mel Smith took the director’s chair, having impressed Lucas with his 1989 romantic comedy, The Tall Guy. Principal photography took place in the Fall of 1993 at Carolco Studios (today EUE/Screen Gems) in Wilmington, North Carolina, where much of Young Indy had previously been shot.

“Mel Smith has a real talent for this kind of movie,” Rick McCallum said at the time. “The technical demands were staggering. We had a cast of 125 speaking parts, with numerous subplots and action happening on several levels at once – on the stage, behind the scenes, in the background. And we had nine weeks to get it all on film.”

A madcap comedy that hits the ground running, Radioland Murders is defined by its remarkable cast. Comedian Brian Benben and popular star Mary Stuart Masterson carry the central storyline as the archetypal foil and straight man (or woman). They’re supported by a gallery of masterful performers, including Christopher Lloyd as the zany sound artist, Michael McKean as the flashy band conductor, Ned Beatty as the bombastic studio owner, and Jeffrey Tambor as the incompetent director.

Smaller roles included a raucous writer’s room populated by comedians Robert Klein, Harvey Korman, Bobcat Goldthwait, and writer Anne DeSalvo. In her last role before her passing, Broadway star Anita Morris played a flirtatious, self-absorbed singer. And to cap it off, true-life icons of the classic stage took cameo roles: actor Billy Barty, singer Rosemary Clooney, and comedian George Burns (then 97), the latter of whom helped to define radio’s golden age alongside his wife and co-star, Gracie Allen.

“Good comedies have a subtle mix of strong believable characters and situations wrapped into a story you care about,” said director Mel Smith. “Laughs alone won’t keep it going. Radioland Murders is as much a mystery as it is a comedy.” That mystery unfolds against the backdrop of the ongoing WBN broadcast, which includes everything from science-fiction adventures, Westerns, situation comedies, a bevy of musical acts, and advertisement jingles to pull it all together. As surprising events take place offstage, we often find the behind-the-scenes action mirroring the emotions of that taking place over the airwaves.

George Lucas used Radioland as a means of refining his time-tested film production methods, now enhanced by emerging digital technology. Footage captured in Wilmington was edited on Avid computers back at Skywalker Ranch in Northern California. Elsewhere on the Ranch, the artists at Skywalker Sound created digital soundscapes. Production sets designed by Gavin Bocquet were extended to full size with digital mattes created by Industrial Light & Magic. Lucas was keen to demonstrate that computer graphics visual effects had an application beyond the fantastic dinosaurs created that year for Jurassic Park (1993). Filmmakers could benefit from these electronic tools in ways that empowered every genre of storytelling, and not in ways that had to break the bank. Lucas insisted the film be made as efficiently as possible without compromising quality, and its budget came out at $10 million, less than a third the average cost of a film at that time.

“George has always said since day one that he wanted this movie to move like gangbusters,” editor Paul Trejo would say. “I mean he wanted the audience to be pressed against their seats from the first reel to the last reel. I think a lot of that had to do with the intrinsic nature of the story, which was that the radio show is just constantly on the air and they’re always racing against the clock to get the next story or script finished.”

Radioland Murders was Lucasfilm’s first new feature in half a decade, and proved an essential testing ground for the behind-the-scenes creatives who would make the Star Wars prequel trilogy. But in the film’s own interests, Radioland was a story from George Lucas’ own heart, one that, like Red Tails (2012), took more than 20 years to complete. And like Star Wars and Indiana Jones, Radioland took its premise from classic forms of entertainment. “I’ve always been fascinated by the fantasy of radio,” Lucas would say, thinking back to his earliest childhood experiences of the power of storytelling. “Radio will never die,” Roger tells Penny near the film’s climax, “it would be like killing the imagination….”

Lucas O. Seastrom is a writer and historian at Lucasfilm.

—

Lucasfilm | Timeless stories. Innovative storytelling.