Producer Miki Herman on the Early Days of Lucasfilm

From Star Wars: A New Hope to Lucasfilm’s First Television Productions

One of Lucasfilm’s earliest employees, Miki Herman had aspired to work in filmmaking and served in many different roles over her ten years with the company. To celebrate Women’s History Month, she joins us to discuss her many Lucasfilm adventures from the intrepid production of Star Wars: A New Hope (1977) to location scouts for the forest moon of Endor in Star Wars: Return of the Jedi (1983) to the company’s first television projects.

May we ask about when you first arrived at Lucasfilm? You were involved with supporting Star Wars: A New Hope producer Gary Kurtz, correct?

I got my start at Lucasfilm actually by volunteering at the American Film Institute [AFI], and I worked as a production manager on a short film with Danny DeVito and Rhea Perlman called Minestrone. I met this woman at the AFI, who was the head secretary, and she left and went to work at the Universal office where Lucasfilm was set up at the time. So I used to call her there and see if she knew of any jobs around. One day, I called and a man named Jim Nelson answered the phone and said, “Well, she’s not here.” So I said, “Well, how about a job for me?” So he hired me to come in to fill in at the Lucasfilm office during Christmas vacation. That’s when I met Gary Kurtz and filled out his Christmas cards. After I left, I called Jim for freebies and favors for the American Film Institute films that I was producing. Jim Nelson was really my mentor, and he was working as a production manager on Star Wars. That was how I started at Lucasfilm. It was really by volunteering at the American Film Institute. So anybody who has a chance to volunteer at a great place like that, it’s just a real sure bet that it’ll fuel your passion with success.

To touch on your background a little more before you came to Lucasfilm, can you talk about what first inspired you to try to get into the field?

My dad had a movie camera and he was always taking home movies. And then when I was in college, I took that movie camera and I started making movies and I really fell in love with filmmaking. I moved to Los Angeles after I graduated from San Francisco State to become a filmmaker. When I would go for interviews at different studios, I found out that you didn’t interview to be a filmmaker. So, the AFI was the place where I got my first taste of making movies other than my home movies and my student films.

And you were a film major at San Francisco State?

I was an art major, and then I got into film, so I was both. I did it in the art department, but I loved filmmaking. It became my passion.

Did you have any favorite films that specifically inspired you or was it primarily just that process of using your father’s camera and things like that?

I always had a camera in my hand, and being in the art department, I learned how to see. The wonderful thing about a training in art is that you learn how to see. So I always had a camera in my hand, either a movie camera or a still camera.

You came and initially helped fill in at Lucasfilm’s offices, but then you ended up doing a lot more as Star Wars was in the thick of post-production and visual effects work. Can you talk a little more about how your involvement with Lucasfilm evolved?

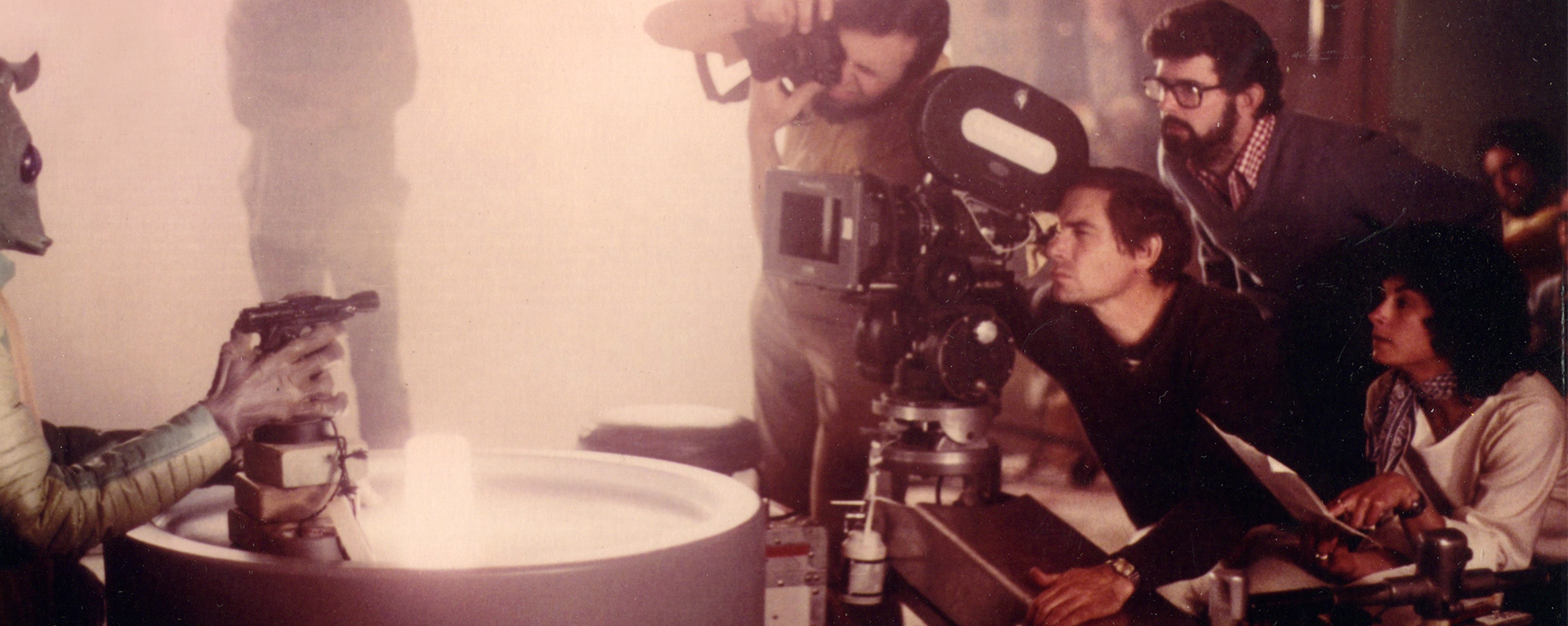

I invited Jim Nelson to the showing of Minestrone at the AFI, and he told me that the Star Wars company had just come back from England, from principal photography, and they needed a production assistant to do some second unit work. I got hired to be the production assistant for some wonderful pick up shots that we did in Death Valley and the Cantina sequence and some close-up shots.

And I’ll tell you a funny story. I was so confident and so excited that when we went to Death Valley, and we first got there and were having lunch, I went ahead and I sat myself down with George Lucas, Gary Kurtz, and Carroll Ballard, the cinematographer, and you could have cut the silence with a knife. I was so happy to introduce myself and to be working with them, and they were so tense. I had forgotten that Jim Nelson had told me not to talk to anybody unless they talked to me. So then I remembered that and I shut up from then on!

One could imagine that things could have been quite stressful by that point in the film’s creation. Could you talk a little more about what your aspirations were? Was this a job you took in hopes of growing in a particular direction? Or were you interested in getting whatever experience you could?

It was a small company at the time, and that was why it was so lucky for me. I got to wear a bunch of different hats and I was just excited to do anything that was needed. And that was a lot of different things, including following George Lucas around during post-production. I wrote down every word that he said. And then I coordinated between the different departments, sound and editorial and Industrial Light & Magic [ILM], the dailies and so forth. And it was so exciting for me. I just thrived on every single second of it.

Was there anything interesting that you recall about George Lucas’ style of work?

He was very, very quiet and very, very private. Only once did I hear him raise his voice at George Mather, the production manager at ILM, because they didn’t have enough special effects shots completed. There was so much stress on George, and Gary, and everybody. Everybody at ILM was working one hundred and fifty percent. When we talk about the Lucasfilm family, that’s when you work one hundred and fifty percent and you bond with people that you’re working with so hard. That was the atmosphere.

As Star Wars came to the finish line, it was quite an intense experience. Did that influence your outlook? You mentioned that Lucasfilm was this young company. Did that experience of seeing a movie come to completion in such a dramatic way influence your thoughts about filmmaking?

I still get goose bumps when I think of that opening shot of the Star Destroyer coming overhead. And when we had the cast and crew screening in Hollywood, I’ll just never forget that. I was overwhelmed and just wanted to be a part of it any way that I could be. I was working with so many talented people that I didn’t really think that I could ever live up to that. And so I followed my way into production and there weren’t a lot of women in film at that time, so that seemed like the safest path for me to go.

Was production something that appealed to you or did it seem like something that you had the most familiarity or direct experience with?

I thought that going into production would be my best foot forward. That was one of the places where there were more women. There were very few women directors, and by this time I gave up being a filmmaker.

We all contribute to the process at Lucasfilm in one way or another.

Right. And I loved that. I loved being part of the process.

Do you recall a sense that Star Wars was going to be as much of a cultural phenomenon as it became?

I think part of the success was due to [Lucasfilm publicity and marketing executive] Charles Lippincott because he went ahead and got all the fans educated and whet their appetite before the film opened. There was already a fan base. And then when the film opened, it was such a phenomenon, and we were still mixing different versions, and the film was still wet from the lab when we got it to the theaters. There were lines all around the block and George and [editor] Marcia Lucas were eating together near the Chinese Theater, and they looked up and they saw this long line around the theater and they could hardly believe it.

It’s interesting to think that at that point you would have still been working with them on the additional mixes and things that were going on.

Yes, and all the foreign versions. I became the go-to person.

To go back for a moment, could you share a little more about Jim Nelson’s working style and how he influenced that group of people at that time?

ILM was just a fun-loving group. When I first met Jim, he just sat at the desk counting every single penny that was being spent. He was very nose to the grindstone, but he didn’t stop. He didn’t discourage people from goofing around and having a good time as well. And he was like the father for us all. He had a really wicked sense of humor as well. He always wore these big Stetson hats and cowboy boots and Indian jewelry. He was a very flashy character, and he also had a lot of Mickey Mouse shirts.

After the release of Star Wars, you became involved in character appearances and events, as well as the archival storage of props and related materials.

That was really a lot of fun. I was kind of the robot roadie. We did public appearances. I took the robots and the characters around to the different photo shoots and TV shows and commercials. Everybody wanted a piece of whatever we had. And because we were a small company, I was the one that did it.

One might imagine that you were always the most popular person in the room when you’d show up with R2-D2!

I was most popular among my cousins, too! They still brag about me!

Could you also talk more about how you became involved in Lucasfilm’s early television appearances and productions?

Because I knew all the props and costumes and special effects shots, that was one of the things that was most helpful to the people that were making the documentaries and so forth. So I would procure all these different things, actors, costumes, and shots so that they could be seamlessly woven into the production.

Ahead of Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back, ILM reorganized in northern California. What was your involvement as work progressed on this film?

Jim Bloom was the associate producer on Empire, and he had lived and worked in the Bay Area for a long time, so he rented the warehouse in San Rafael for ILM. And as the key personnel came up, like Richard Edlund and Dennis Muren, the stage had to be developed. A lot of new equipment had to be built and Gary Kurtz mostly coordinated that whole thing. George was busy writing The Empire Strikes Back. Actually, that started before we even moved up. I remember interviewing writers at the Universal office, including Leigh Brackett and Larry Kasdan. It was very exciting to move up north. I had gone to San Francisco State and I had lived there for many years. Helping set up the new studio was another hat I wore.

How did working on Empire compare to the first Star Wars?

I was production coordinator at ILM for The Empire Strikes Back. It was an amazing experience compared to Star Wars. We had so many more shots and they wanted to outdo themselves. They were challenging themselves to make the shots more spectacular and to invent more innovative equipment and different special effects shots. When you think about Empire with the snowspeeders and the walkers and Yoda… I think it’s my favorite movie of the trilogy.

Raiders of the Lost Ark followed Empire, and you were involved with second unit production on the film. That included a number of location shoots including San Francisco City Hall.

We also had the seaplane, then we went to Stockton for the exterior of the college campus. And I think we even shot one insert at [sound designer] Ben Burtt’s house with Indy throwing the gun in the suitcase!

As you continued to wear these different hats, did your own ambitions change?

All I remember was that after The Empire Strikes Back, I really wanted to get into live action. I was kind of tired of the special effects, it’s so grinding. My aim was to do more in live action, and I love location scouting.

With Star Wars: Return of the Jedi, you got to go on some interesting adventures as the main woman in the field. In particular, you scouted the location for the forest moon of Endor. How would you describe that experience?

It was heaven. I scouted almost every redwood forest from Santa Cruz to British Columbia. I was in so many cathedral groves. Being among those towering redwoods was so inspirational. For the Endor bunker, it was challenging to find a place where we could blow up trees and build everything. We found a contact, Lenny Fike, in Crescent City who knew people at the Rellim Redwood Company. We found a place where the trees were going to be cut down or were deceased. We also shot in some gorgeous National Parks. We did some plates for ILM for the speeder bikes at Pamplin Grove and Nature Conservancy. That was probably the best time that I had going to those forests and scouting those locations. It was just wonderful. I was in planes, trains, automobiles, helicopters, barges, seaplanes… everything.

It seems poignant that you would’ve had a camera in your hand to take reference. And you mentioned earlier that you’ve always had a camera in your hand and so it must have been a photographer’s dream.

I would get these big sheets, white cardboard sheets, and I would do collages of all the pictures that I took for George to see.

As you traveled around, one imagines that you didn’t say you were working on Star Wars.

I worked undercover! And speaking of undercover, when we were still at Universal back on A New Hope, Gary Kurtz asked me to research robots. So undercover, I wrote to these different robotics societies. There wasn’t much then compared to the robots that they have now. That was really interesting.

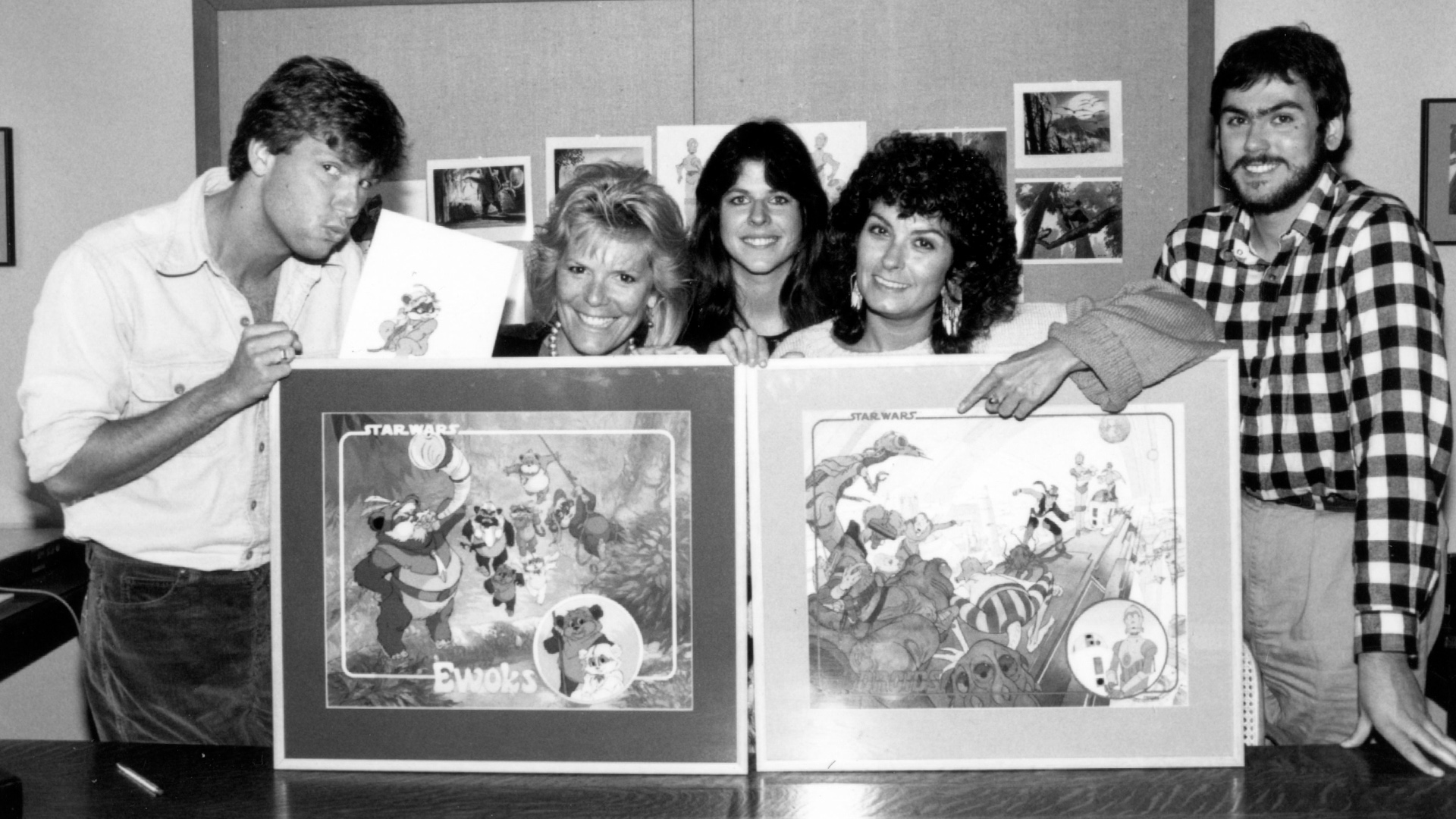

After Return of the Jedi, robots came up again as you began work on the Droids animated series, as well as the Ewoks series. How did you become the producer for these television shows?

George had asked me to take it on. It was really fascinating too. I learned so much. George wanted us to explore fairy tales. Bruno Bettelheim wrote this book, The Uses of Enchantment. We did a lot of research and we really dug deep into fairy tales. For Ewoks, he wanted that to be soft and cuddly. And for Droids, it was kind of the Mad Max period, and he wanted that to be very edgy. We had challenges with Standards and Practices. Network television goes through every script, and if there’s something called imitative action, you know, like a child would try to fly like Superman or something like that… but George wanted us to make it tough. And so that was one of our challenges, how to get around Standards and Practices. And then when I left Lucasfilm, he asked me if I wanted to write a book about Standards and Practices!

Lucasfilm was partnering with Nelvana Studios in Toronto. They had worked on the animation in The Star Wars Holiday Special. What was working in animation like?

I got to go to Japan, Hong Kong, and Korea to tour these animation companies. And then finally, we did pick Nelvana, but we considered Hanna-Barbera among others. Everybody wanted it. But then I just felt so comfortable with Nelvana after I worked with them on The Holiday Special. They did a really great job. I also love the music that Taj Mahal did for the Ewoks show.

It’s special in a way that Droids and Ewoks are back on Disney+ and kids are watching the shows again.

Yes, it is, and I’m also really enjoying The Mandalorian because I get a kick out of seeing a lot of the shots that we did on Star Wars with the Banthas and Boba Fett and the Sarlacc. I’m getting a kick out of that too.

You once said that George Lucas would give people the ball and let them run with it. All these people at Lucasfilm who started at these relatively entry-level positions had the chance to learn and climb. Can you talk about how that happened and how you think this reflected on the creativity within the company?

We were all very enthusiastic, talented people. George couldn’t really go wrong because anybody that he wanted to give the ball to, he felt assured that it would not be dropped. He would do extra things, like he sent [art director] Joe Johnston to the U.S.C. cinema school. He became a famous director. There was a lot of trust and a lot of bonding. When you work with people that give one hundred and fifty percent, they’re going to be trustworthy.

You left Lucasfilm in the mid 1980s, so you had about a decade with the company. Could you talk a little bit about how your hats continued to change in your career?

I came down to Hollywood and I wanted to produce a live action movie. I had a development deal at Paramount with Danny DeVito and Rhea Perlman. Rhea’s sister Heidi Perlman wrote a script and [former Lucasfilm executive] Sid Ganis was the head of production at Paramount. He greeted us very lovingly, but unfortunately, the script went into turnaround. At that point, there were a lot of strikes, like writers’ strikes and Screen Actors Guild strikes, and there wasn’t much going on in Hollywood. So I figured that I better change careers. It just felt like it was time. It was a difficult transition for me, too, because so much of my identity was wrapped up in Lucasfilm.

After I left, I kind of went into a deep dive about who am I really? I actually got kind of depressed and I went to a therapy group and it helped me a lot. I decided that I would be a good therapist, and went back to school and I got my master’s degree in psychology counseling, and then I got my Ph.D. in clinical psychology. I would see people that were in the film business, they would say, “Oh, you were so smart to get out and do something worthwhile.” And then the people in the psychology business would say, “You did that, why do you want to do this?” You never know when you get on a road where it’s going to take you.

And are you retired now?

Yes, I retired in 2017. I always tell people that whether producing movies or being a therapist, the only difference is that in therapy you only have to understand the problems, you don’t have to put out the fires.

What have you been up to recently?

I’m a believer in lifelong learning and an arts lover. In addition, I volunteer at The Skirball Cultural Center, and facilitate art projects in the family art studio.

Lucas O. Seastrom is a writer and historian at Lucasfilm.