Director Laurent Bouzereau on Creating Music by John Williams

The feature documentary about the celebrated Star Wars and Indiana Jones composer is now available on Disney+.

Laurent Bouzereau experienced some of John Williams’ most iconic movie scores before he had even seen many of their accompanying films. The director of the feature-length documentary Music by John Williams — which premieres today on Disney+ — grew up in Paris, France in the 1960s and ‘70s during an era when American films like Jaws (1975) and Star Wars: A New Hope (1977) didn’t arrive in French cinemas until months after their original release.

“My dad often traveled to America and he would bring me back the soundtracks,” Bouzereau tells Lucasfilm.com. “I got Jaws and Towering Inferno [1974] and all these films. I started to fantasize about those movies in a way that was so musical and so intimate. I made my first trip to America in the summer of 1977, which was the summer of Star Wars. The family I was staying with asked what I wanted to bring back home as a souvenir of the trip — an American flag? A frisbee? A baseball mitt? I said I wanted a soundtrack by John Williams. He literally became my musical muse.”

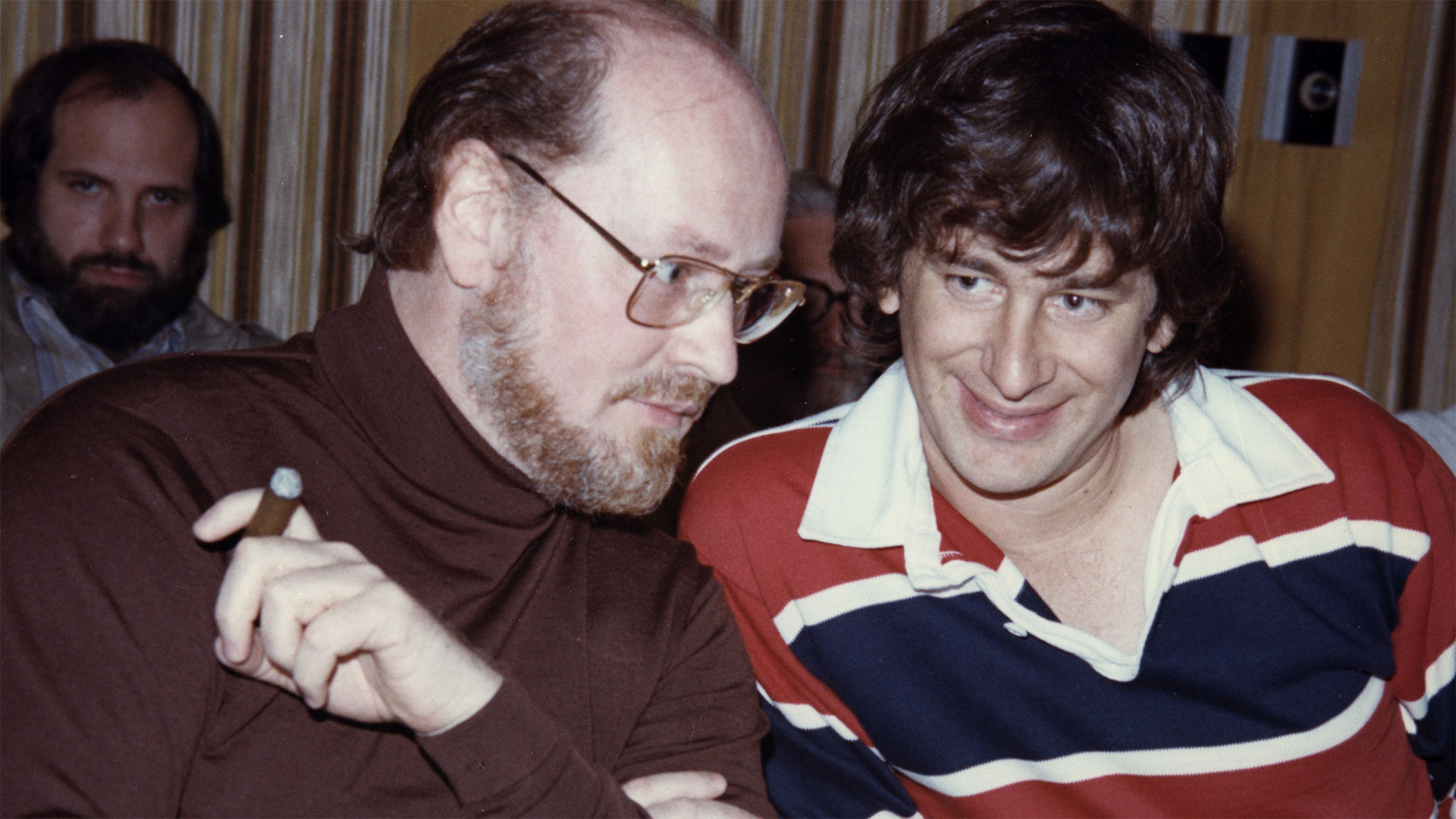

With this background alone, one is hard-pressed to imagine a filmmaker better suited to direct Music by John Williams, which charts the continuing story of its namesake’s legacy in not only movie scoring but the broader world of music in general. Yet Bouzereau’s connection to the work of his musical hero would only deepen. By the 1990s, the Frenchman had become an established documentarian and film historian working in the United States. He was soon recruited by Universal to create a retrospective film about Steven Spielberg’s 1979 comedy, 1941. The project afforded him the chance to meet not only Spielberg, but also John Williams, who had been the film’s composer.

“I was less intimidated meeting a star actor than meeting those two men,” Bouzereau recalls. “I didn’t want to come across as a fanatic, but rather as someone who really understood their world and their work. Steven and I started talking and made an immediate connection and one that I’m grateful has continued to today. And it was great to talk with John about a score that is lesser-known but still brilliant. 1941 is almost like Steven’s first musical in a sense. That score reflects the chaos going on in the story. We had a lot of fun and I felt really inspired by both of these men.”

Spielberg and Williams first met in the early 1970s when the former sought out the composer to score his first theatrical feature, The Sugarland Express (1974). Spielberg had been an avid movie score fan for years, and Williams, at that time already in his early 40s, had been an active composer in film and television for more than a decade. Their partnership over the next 50 years forms an important thread in the documentary’s narrative. It is, in fact, where Bouzereau chose to open the film: with the equally ominous and ubiquitous thematic score for their second collaboration, Jaws.

“I always write a script and I was trying to find a way to engage audiences right off the bat,” the director says. “Jaws is really a part of pop culture, so to start with that, everyone knows what you’re talking about. Even young people who may not know John or weren’t born at the time will hopefully be hooked by this part of the story.”

It was Bouzereau’s ongoing collaborations with Spielberg and Williams that afforded him the opportunity to tell this story in the first place. After the initial project about 1941, he continued to produce retrospective documentaries, many of them about productions from Spielberg’s company, Amblin. “When I started working at Amblin years ago, John Williams had a bungalow where he’d work,” says Bouzrereau, “and I’d go there and hang out with [music editor] Ken Wannberg. John would be in his room composing, and I’d be talking with Kenny and he’d tell me all these stories and play things on the piano. All of that informed me about the process. So I feel like I’d been preparing myself for many years for this film.”

Getting the film underway, however, took years of persistent effort, in large part because of Williams’ reluctance to have his own story told. Bouzereau continued to work with him on individual projects, but each time he raised the topic of doing a film about Williams’ life and work, the composer humbly turned him down. Bouzereau tried again in 2022 as Williams celebrated his 90th birthday.

“I interviewed a lot of people who worked with John for a little sizzle reel just wishing him a happy birthday,” Bouzereau explains. “But when I found myself across from all of those people who had worked with him, I said, ‘I’m sorry but I’m going to ask a lot of questions.’ In essence, the documentary started to form during that time.”

Momentum came in June of 2022 at a gala event in Williams’ honor at the Kennedy Center in Washington DC. Attendees included Steven Spielberg, producer Frank Marshall, Lucasfilm president Kathleen Kennedy, and Bouzereau himself. “Obviously, the history between Kathy, Frank, Steven, and John is gigantic,” Bouzereau points out. That night, the filmmaker approached Spielberg about the documentary concept, and the latter took the idea to Williams, who at last agreed.

By coincidence, Ron Howard’s Imagine Documentaries had approached Bouzereau about a Williams documentary around the same time, thus helping solidify the film’s production team along with Amblin, Marshall and Kennedy, and Bouzereau’s own Nedland Media. But as plans came together, Williams once more showed reluctance to proceed. “I found myself at Amblin one day filming for another project,” Bouzereau recalls. “My crew was in one room and my computer was in another, and as I stepped out to go to my computer, there was John by himself.

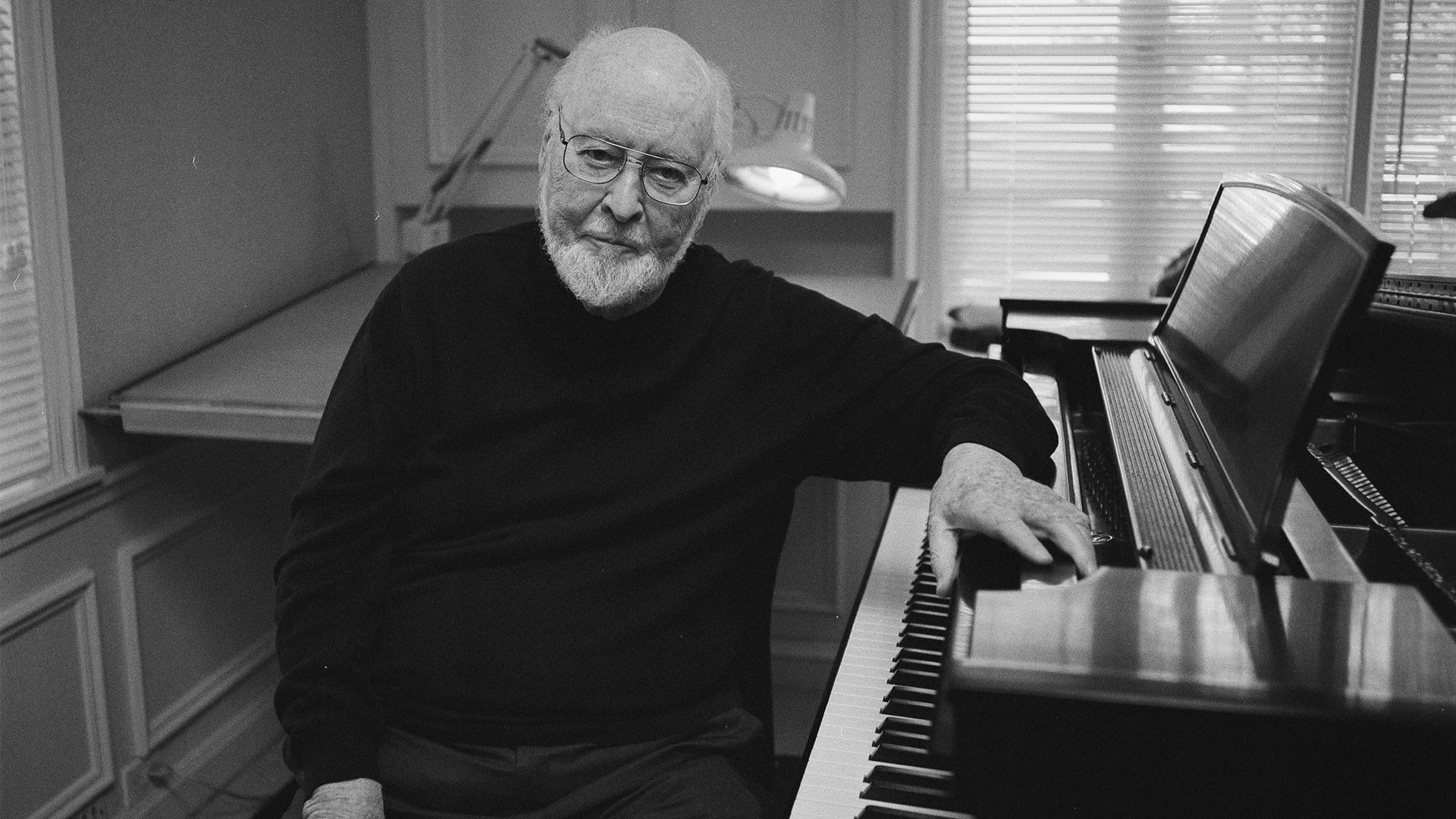

“It was the weirdest thing to bump into him,” Bouzereau continues. “He told me, ‘I’m not sure about the documentary.’ I said, ‘Why? Everybody loves you!’ And he said, ‘Nobody cares about my life story.’ I told him, ‘This is really about your music and your musicians.’ I think it helped him to understand that I was approaching this through music. He realized that the goal was to show the musical journey first and foremost. Then I could ask him about anything as long as it was through the lens of music.”

Finally diving into production, Bouzereau and team were able to uncover a slew of rare material from Williams’ personal collection, Lucasfilm’s vaults, and beyond. Among the archival treasures in Music by John Williams is never-before-seen home video footage shot by Steven Spielberg during the respective scoring sessions of each of his films. The team was also able to have rare access to Williams, including private sessions at the piano where the composer discussed elements of his compositions.

“I had asked John about doing sessions on the piano for the film, and he’s very shy about playing stuff like that,” Bouzereau notes. “I had given him a list of pieces at first, but then we decided to just have fun. John was just playing and then Steven crashed our interview! I didn’t know he was going to do that, but I’d seen him earlier that morning and he asked what I was doing, and as soon as I told him, I could see the wheels turning. So then I was with John and Steven suddenly came in. I would never have asked him to do that, but the fact that he did made it really special.”

Following Williams in his routine also meant attending concerts and rehearsals with symphonic orchestras. “I don’t think there had really been cameras with John behind the scenes at the Hollywood Bowl,” says Bouzereau. “He gets out his baton, puts on his jacket. I had never seen that before. That was a window into a process that fascinated me, and if I’m fascinated, then hopefully the viewers will be, too.”

The story would be incomplete, of course, without speaking to musicians. “I only know the film world,” Bouzereau points out. “But when you’re making a film, if you’re not curious, if there’s no sense of discovery on the part of the filmmaker, then you might be setting yourself up for something uninteresting.” Comparing it to the experience of capturing the making of Spielberg’s West Side Story (2021) with dancers and singers, Bouzereau and his team worked up close with the San Francisco Symphony and the audience at the Hollywood Bowl, among others. And they interviewed the likes of cellist Yo-Yo Ma, violinists Anne-Sophie Mutter and Itzhak Perlman, and conductor Gustavo Dudamel.

“The thing that really stood out for me was their sense of humor,” Bouzereau observes about his musically-inclined subjects. “All of the musicians were coming at it with a sense of fun. These people have an interesting relationship with John. It’s based on their mutual love of music, of course, but they’re also extremely funny. That surprised me. I thought they might be very scholarly and I would have to be serious.

“There is amongst musicians a strange sort of language that has to do with humor,” Bouzereau continues. “They do take themselves seriously. They’re all about the work and having a good time doing it. They don’t have to prove anything to one another, so they can have levity. When it comes to the work, there’s a different kind of intensity. We shot Anne-Sophie onstage with John rehearsing, and John is making jokes and they’re laughing. Then she performs and it’s the most intense thing.”

The emotional power and expression of the music remains at the heart of Music by John Williams, and the film does not shy away from posing questions about the creation of music in our present culture. At one point in the film, Williams himself notes that it’s “a time for questions” and “a time for wondering” in the realm of music. Bouzereau addresses the subject with frankness.

“John legitimized film scores,” the filmmaker says. “We discuss John and the Boston Pops in the movie, including how, at one point, some of their musicians had refused to play music they felt wasn’t legitimate. John has changed that dialogue about film music completely. He also has a love for the orchestra and the musicians and he gets really excited with casting certain musicians for the score. John has kept this music alive in Hollywood, but who will take it on after him? I hope the film can help inspire people.

“We had a premiere at the Chinese Theatre, which was fantastic,” Bouzereau continues, “and then the next day, Frank [Marshall] and I got an award at the Newport Beach Film Festival. When we were there, three kids came up to me. One of them said, ‘I saw the film…and I just wanted you to know that I played the piano as a younger kid and I abandoned it, but after seeing the film, I want to play the piano again.’ And the two others said, ‘We’re studying to be filmmakers and now we want to do documentaries.’ It was that impactful on these kids who obviously did not grow up in the same way that I did. That made me really happy. If the film accomplishes that, then we’re passing on the baton, literally!”

Lucas O. Seastrom is a writer and historian at Lucasfilm.

—

Lucasfilm | Timeless Stories. Innovative Storytelling.