Lucasfilm’s Mike Blanchard Looks Back on Three Decades of Filmmaking Adventures

The vice president of post-production celebrates his retirement in March of 2024.

Mike Blanchard, Lucasfilm’s vice president of post-production, is retiring after nearly 30 years with the company.

Blanchard’s Lucasfilm journey began at Industrial Light & Magic in the early 1990s when he spent over a year as a production assistant with the visual effects house’s commercial division. It was 1995 when Blanchard was then hired to join Lucasfilm’s post-production department – at the time known as JAK Films – to assist with the completion of The Adventures of Young Indiana Jones. That temporary role blossomed into a 29-year odyssey that gave Blanchard a front row seat to George Lucas’ groundbreaking efforts in jumpstarting the modern era of digital cinema.

“Just driving to Skywalker Ranch on that first day, I don’t even know how to describe it,” Blanchard tells Lucasfilm.com. “It’s the most beautiful place on Earth, and now I’m working there? I pulled right up to the Main House, and it was pretty overwhelming. I was nervous. This was a short-term job and I needed to be on my game.”

A San Francisco native, Blanchard had developed an affinity for the movies of Francis Ford Coppola, among them The Conversation (1974) and Apocalypse Now (1979). When he learned that Coppola and other filmmakers like George Lucas worked in the Bay Area, Blanchard was inspired. He attended San Francisco State University as a film student, working odd jobs in the local industry to pay his tuition. Upon graduating, Blanchard considered entering the graduate cinema program at the University of Southern California, but made different plans after a chance meeting with a well-known producer.

“My girlfriend at the time, her father knew Kathy Kennedy’s father,” Blanchard explains. “He offered to see if she’d be willing to have a meeting with us. She agreed, and we drove down to the Amblin offices. The amazing thing was that even though Kathy had a horrible cold that day, she still took the time to speak with us for over an hour. Based on what I shared about my aspirations, she told me that I needed to get a job in the business and work my way up, rather than accumulate additional college debt. She gave me spot-on advice for how to maneuver into this world.”

Another valued insight Blanchard learned from Kennedy was that “it’s important to understand everyone’s role and how they contribute to the overall filmmaking process,” as he puts it. In addition to his production assistant role on the shooting stages at ILM, he’d work at a post-production house and even a video game company before joining Lucasfilm full-time. “I learned as much as I could about the business while also determining which part inspired me the most,” Blanchard explains.

His mixed background proved useful from the start. Blanchard remembers how during one of his first weeks in the Lucasfilm post-production office, George Lucas threw him an unexpected assignment. “He came out of the cutting room and excitedly told me, ‘We need you to shoot an insert shot so that we can place it in this sequence.’ He would do things like that all the time. We’d make videomatics, just by shooting something temporary to portray the action as a reference for the actual shoot.”

This particular insert depicted Indy and a friend walking down a country road, away from the camera. “George told me, ‘Get one of the guys from the firehouse and they’ll take you up to the ridge,’” Blanchard continues. “I was so new I don’t think he knew my name yet. He said, ‘This is like film school, just grab a camera and go shoot it!’ [laughs] I remember coming home to my wife and saying, ‘This job is going to be an incredible experience.’”

Blanchard and his colleagues on the relatively small JAK Films crew worked alongside Lucas during what was arguably his favorite part of the filmmaking process. “It’s where George loved to be,” as Blanchard notes. “There was a lot of pressure on him running a company with thousands of employees. But editorial was home. This is where he could be an artist or a film student again. He liked to direct the movies in post. It was his sanctuary. It was such a privilege to be in his orbit in that happy place for him.”

The JAK crew “had to wear a lot of hats” as Blanchard explains. “If you didn’t know something, you had to learn it. When George, [producer] Rick McCallum, or an editor would throw me something, I had enough knowledge to get started and then dive into further research. I think that’s one of the reasons I ended up staying for so long. Whenever new things came up, I could help marshal it along. In an era when people tend to specialize, there’s something to be said for having a broad understanding to help piece everything together in a more efficient fashion.”

That broad understanding was no more valuable than during work on the Star Wars prequel trilogy, for which Blanchard assumed the role of technical supervisor. After decades of pioneering new digital tools that influenced specific aspects of the filmmaking process, George Lucas was ready to apply Lucasfilm’s advancements across the board and make a Star Wars film with a completely digital toolset. The director wanted to demonstrate how such innovations could improve the filmmaking craft, empowering filmmakers to be more easily creative and apply their imaginations in an uninhibited fashion.

It was up to Blanchard and his colleagues to make it possible on a day-to-day basis. This strayed beyond the confines of post-production, from computer-animated pre-visualizations during pre-production, to a digital camera that captured high-definition footage during principal photography, to the fully-digital projection of the movie upon release. For many of these steps, only prototypes were in use at the time, and they didn’t integrate well with existing tools.

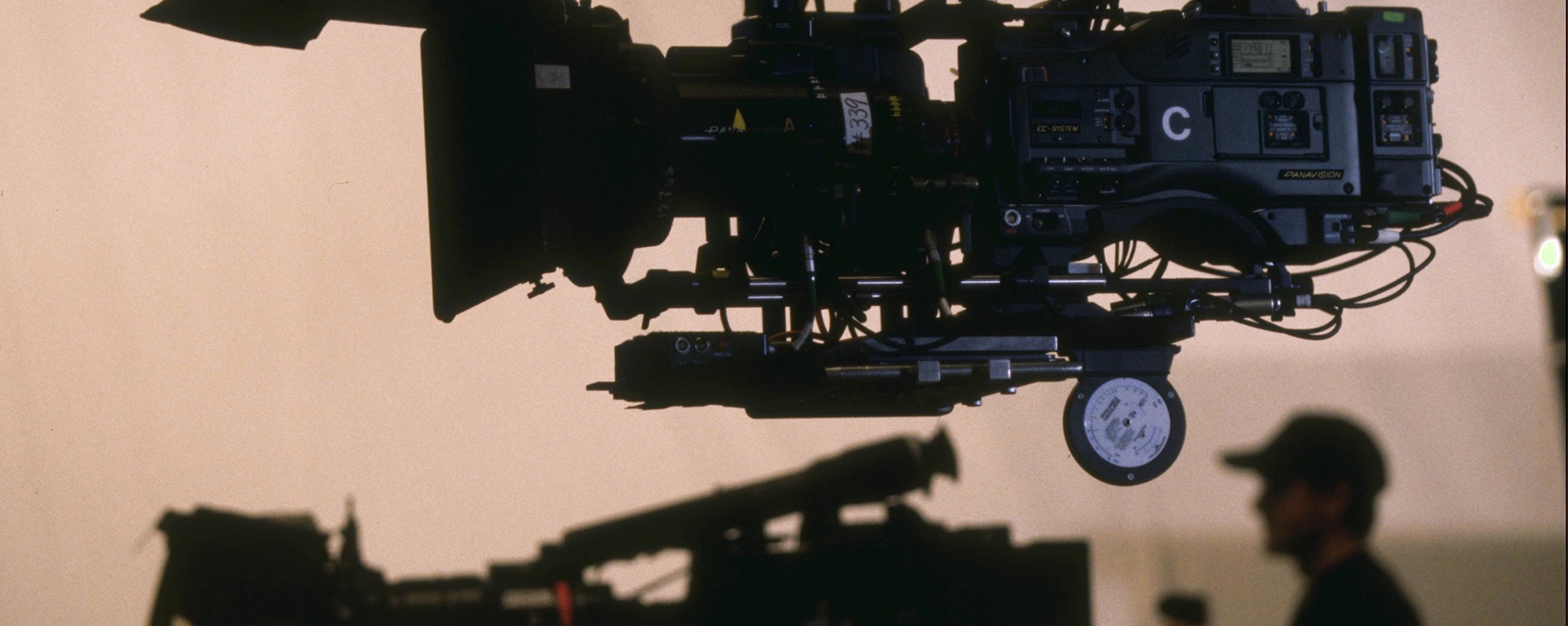

Beginning with the Star Wars Special Edition (1997) releases, then Star Wars: The Phantom Menace (1999) and Star Wars: Attack of the Clones (2002) as the first all-digital blockbuster, Blanchard manned the front lines (read more about his work on Clones specifically at StarWars.com). He haunted industry conventions to recruit partner companies to help develop individual tools. Among countless projects, he collaborated with Sony, Panavision, and the Lucasfilm onset crew to devise a new camera system and workflow that would soon become standard-operating-procedure on movie productions around the world. Blanchard partnered with his former colleagues at ILM to enhance their digital dailies process and helped create fully digital masters of The Phantom Menace to be screened with some of the first DLP cinema projectors made by Texas Instruments.

From one new challenge to the next, Blanchard had little time to reflect on it all. Looking back now, he explains that what got him through those pioneering days was “loyalty” to George Lucas. “Don’t get me wrong. It was hard,” he says. “We had a small team. What George asked for was difficult because he was so far ahead of everything. But there was no confusion about what we were supposed to do. We had a clarity of purpose that came straight from George. We didn’t want to let him down. For me that was it. Once we knew what he wanted, we had to do everything we could to get it done.”

Throughout the intrepid adventure that was the prequel trilogy, Blanchard remained faithful but cautious, with the ever-present thought that something would go irretrievably wrong and foil Lucas’ vision. But their tireless efforts paid off, and Lucas’ example continues to inspire the diverse approaches to filmmaking methods today.

Blanchard’s own Lucasfilm journey continued to have many highlights. Among his personal favorite projects was collaborating with Lucas and the late writer J.W. Rinzler on the book, Star Wars: Frames, which was yet another distinct learning opportunity. He also fondly recalls the companion historical documentaries made for the DVD release of Young Indiana Jones. “Nobody but George could ever come up with that idea as a way of teaching people history,” Blanchard says. “We made about 94 documentaries. His idea was that people are busy, and not everyone knows much history, so what should they know about art or psychology or this aspect of World War I in 25 to 35 minutes? We had an amazing crew working on those films. Normally in documentaries you move from job to job, and it can be really hard to find work. This was a very special opportunity for this core group of filmmakers to work together for about eight years.”

History was top of mind again when Blanchard and his colleagues met the heroic Tuskegee Airmen during production of Red Tails (2012). America’s first Black military pilots during World War II visited Skywalker Ranch to consult with the film’s actors and crew. “Just to be there and listen to them was very special,” Blanchard recalls with deep reverence. “The veterans just wanted the actors to understand what the planes were like, what the missions were like, what it felt like to be in combat. They all spoke to the fact that, at the heart of it, they just wanted to fly. It was this passion they had. They were told they couldn’t, but they did it. You could hear a pin drop as they shared their stories. It doesn’t take a lot of imagination to realize how amazing this was. There’s no way that anyone who was there will ever forget it.”

Over a decade of Blanchard’s tenure came after Lucasfilm’s acquisition by the Walt Disney Company in 2012, allowing him to reunite with Kathleen Kennedy for a new odyssey of Star Wars productions across film and television (not to mention Indiana Jones and Willow). With so many projects overlapping, Blanchard has enjoyed collaborating with new filmmakers, including directors like Rian Johnson, Ron Howard, J.J. Abrams, Gareth Edwards and producers like Ram Bergman. “I loved the dynamic between Rian and Ram, the way they work together is fantastic. It’s really a model for what a director and producer team can be,” Blanchard explains. “On Solo, I finally got to work with Ron Howard, and it’s absolutely true that he’s the nicest man in show business. So collaborative, and aware that everyone is there to help him get where he wants to go and he’s so appreciative of everyone’s efforts.”

As filmmaking technology has continued to evolve, Blanchard’s past experience has afforded him a distinct view of the newest tools. He describes many instances in recent years, including the development of the ILM StageCraft volume for The Mandalorian, when he could recall George Lucas imagining such an innovation years before.

Looking back on his tenure, Blanchard notes that maintaining “Lucasfilm’s DNA” has remained very important to him. “As the years go by, naturally there are less people in the company who worked with George. But there’s still a reason why we’re in Northern California, and there are so many great people here who respect that. There’s a reason why George came here, and it has to do with that rebel spirit. It’s important to think about that from time to time. Why are we here? What has it taken for Lucasfilm to endure for so long and survive a crazy business over all these decades?”

As he says farewell to his own part of Lucasfilm’s continuing story, Blanchard looks forward to “retraining my mind to be present,” as he says. “I’ve spent my career trying to get out in front of problems and always have multiple contingencies in place if and when they arise. I’ve been under deadlines every day. It’s time to let that go. I’m looking forward to having no plan and letting each day unfold.”

Lucas O. Seastrom is a writer and historian at Lucasfilm.

—

Lucasfilm | Timeless stories. Innovative storytelling.