Lucasfilm Originals: THX

The Audience is Listening

What began as a project to improve the quality of Lucasfilm’s new sound-mixing facility quickly snowballed into a decades-long effort to improve the movie-going experience for everyone.

In 1982, just about every part of Lucasfilm was busily at work on Star Wars: Return of the Jedi (1983), set for release the following year. The physical production was underway in England and on location in the United States. Industrial Light & Magic (ILM) was embarking on its most ambitious visual effects project to date. The Computer Division’s graphics group (which later became Pixar Animation Studios) was working on a brief computer-generated effect of the forest moon of Endor and Death Star. And over at Sprocket Systems – Lucasfilm’s post-production division which later became Skywalker Sound – the crews of editing and sound personnel were moving into a new home.

To be ready for Jedi and subsequent productions, Lucasfilm had constructed a new building in San Rafael, California where ILM, the Computer Division, and much of Lucasfilm occupied a series of work bays and office complexes along Kerner Boulevard. Dubbed “C Building,” the structure boasted a shooting stage, editing facilities, rooms for computer servers, and a large theater designed as a state-of-the-art sound mixing room.

Tomlinson Holman was a skilled audio engineer and scientist largely responsible for the design of the theater. As a creator of preamplifiers and fascinated with acoustics, he’d joined Lucasfilm in 1980. In the process of enhancing the setup for Sprockets’ new theater, Holman invented a complex system of arranged speakers to best fit the architectural space within the theater. Using an intricate crossover network that integrated equipment with the room’s unique acoustics, it became perhaps the best quality system anyone could remember hearing.

Sprocket Systems sound-mixed Return of the Jedi in the room, the first Lucasfilm production mixed in northern California. Visiting filmmakers and studio executives were astounded at what they heard. Holman took to calling the sound system “THX,” standing for “Tomlinson Holman Crossover,” but also a coy reference to George Lucas’ first theatrical feature film, THX 1138 (1971).

Although Lucasfilm’s own facility was among the best in the world, this would matter little if the experiences of the audience in their local movie theaters were of poor quality. No uniform standards existed for theaters, either for speaker systems or visual projection. Many were in disrepair, plagued by ambient noise, reverberation, or dim screens. To ensure that the audience experienced the film as they had created it, Lucasfilm commenced a Theater Alignment Program (known as TAP), which urged theater owners to improve their facilities.

The THX standards aimed to enhance the sound and picture quality and ensure consistency between every seat in a movie-house. Speaker systems were designed to best fit the room’s unique acoustics. New spaces were designed to limit reverberation, allowing audiences to fully engage with every nuance of a soundtrack. From mixing stage to theater, THX was about creating the best movie-going experience for everyone.

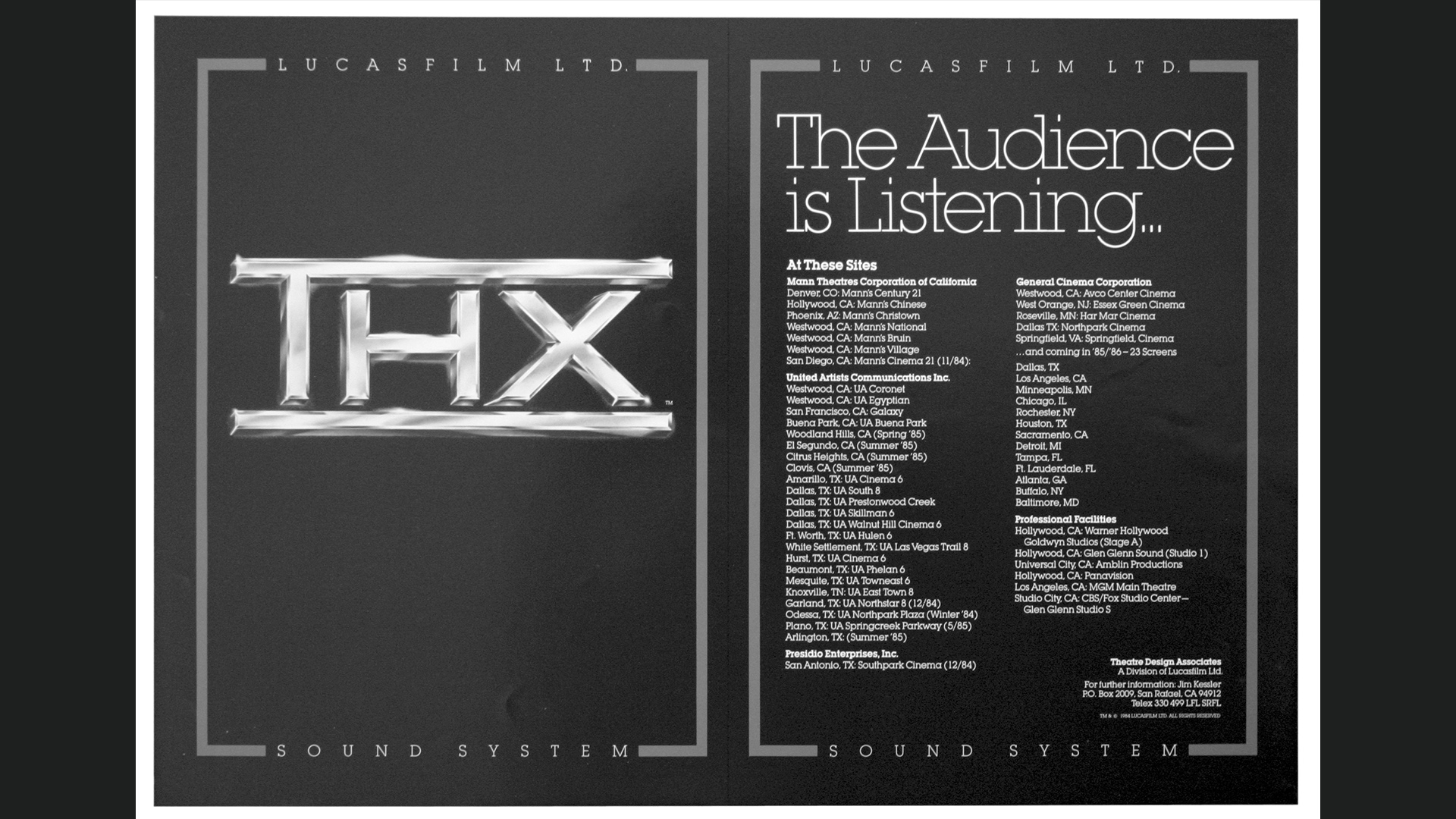

For the release of Jedi in 1983, Lucasfilm representatives visited some 100 theaters to inspect their technical systems and help improve their specifications. Four movie houses in the United States would opt to fully install their own THX sound system, becoming the first certified theaters. To introduce the system, Computer Division scientist and audio artist James A. Moorer created an ear-catching sound known as the “Deep Note.” The piece of digital music showcased THX’s nuanced quality.

Over the years the THX and TAP programs grew, with hundreds of certified theaters around the world, and contracted field agents who made routine visits to inspect their system quality. THX would offer elaborate home systems too, as well as certify home video releases. The Deep Note and logo became ingrained in popular culture. Lucasfilm operated the division for some 20 years before THX was sold, and it has continued to this day.

—

Lucas O. Seastrom is a writer and historian at Lucasfilm.