Lucasfilm Originals: The EditDroid

At Lucasfilm, the Craft of Filmmaking is Always Subject to Improvement

To celebrate the 50th anniversary of Lucasfilm in 2021, “Lucasfilm Originals” is a blog series exploring technological innovations from long past to the present day.

George Lucas never stopped thinking like an editor. From his time as a film student at the University of Southern California, he demonstrated a keen ability for arranging sound and visuals. As he became a feature filmmaker and gained writing and directing credits, Lucas continued to handle his own films in the editing room in collaboration with the post-production team.

But over the years Lucas grew increasingly frustrated with what he called the “19th century process” of traditional film editing. Working with a linear system, editors physically cut and spliced pieces of film and re-attached them with tape and glue. Assistants hunted for discarded pieces inside trim bins filled with celluloid. It was a laborious process that for Lucas risked inhibiting his creative freedom.

By the late 1970s, Lucas was among the filmmakers looking for a better option. Computer systems were already being used to edit videotape. Perhaps this new technology could be adapted for a feature film?

Lucasfilm’s computer group was established in 1979, and later became a full-fledged division. Computer scientist and artist Ed Catmull had been recruited from the New York Institute of Technology to form a group for the research and development of computer-based filmmaking tools. Applications would include digitized film scanning and graphics, digitally-processed sound, and a non-linear editing system.

Catmull would recruit former colleague Ralph Guggenheim to help oversee non-linear editing. They envisioned a system by which motion-picture film could be digitally scanned into a computer, edited in a way that allowed for random, instant access of clips, and re-printed to film at the end of the process. They received input from traditional editors as the system was designed to adapt the standard workflow of the older tools.

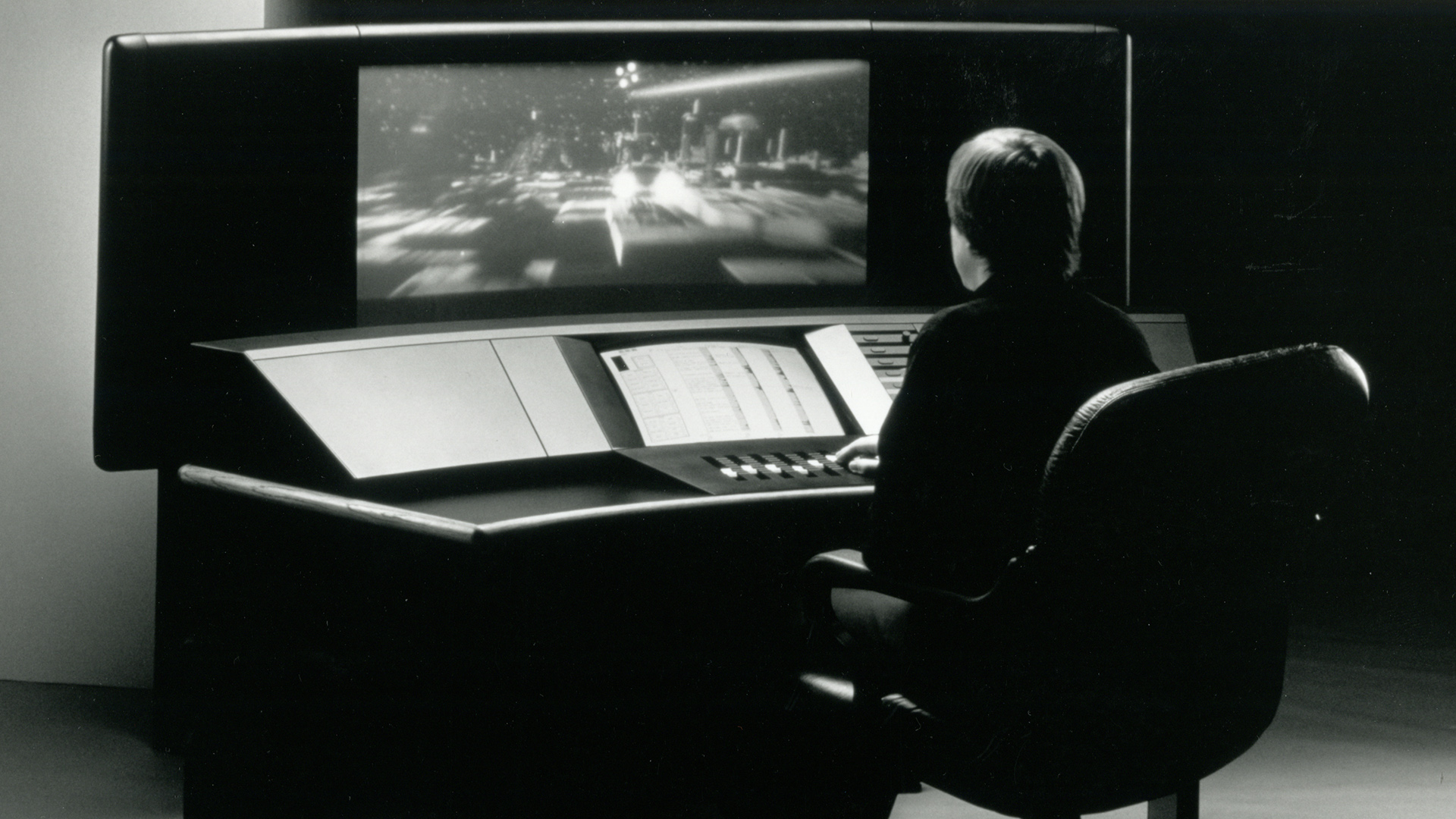

The Lucasfilm team decided that videodiscs – a large format disc similar to a phonograph record – were ideal for storing and accessing image and sound elements. Through multiple versions by trial-and-error, the team spent four years crafting a functional system with videodisc storage, a SUN microcomputer display, and specially-designed touch-pad.

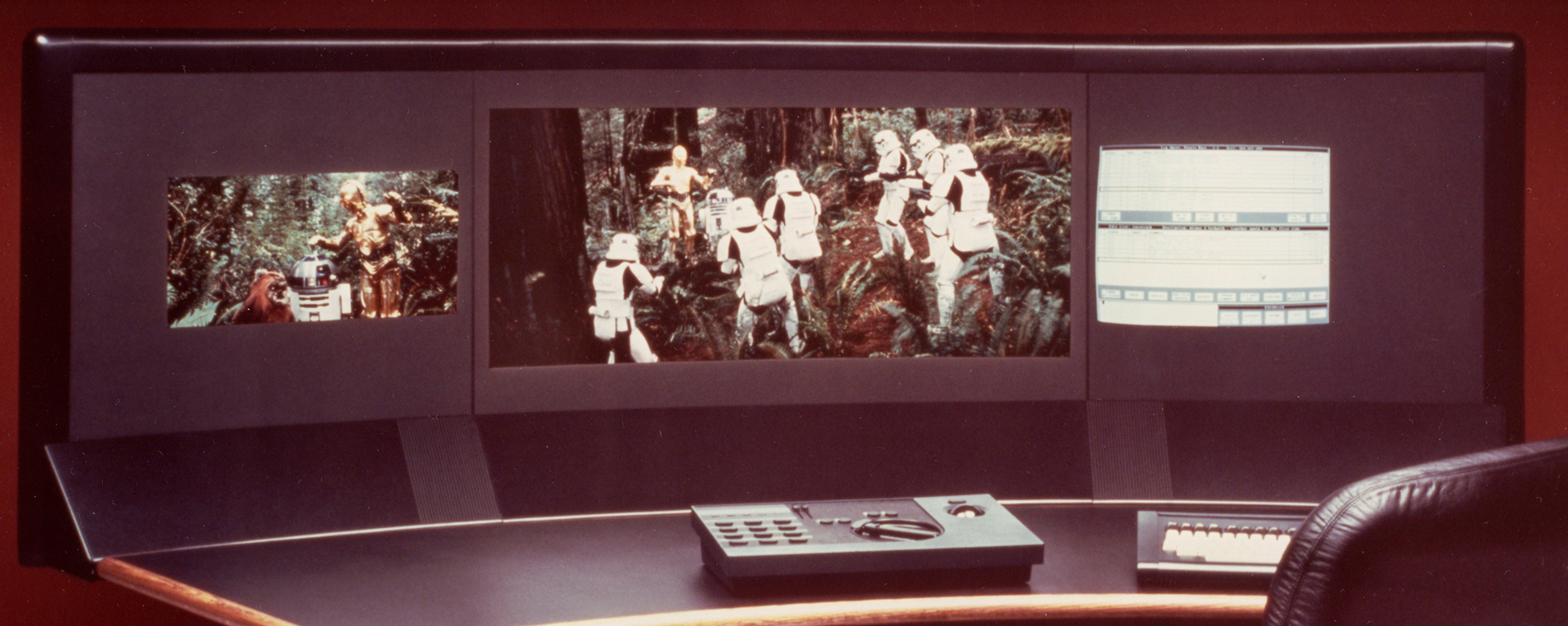

Dubbed the “EdDroid,” and later the “EditDroid,” the system made its debut at the National Association of Broadcasters convention in 1984 (the same year as the launch of Apple’s Macintosh personal computer). Attendees previewed the sleek imposing console informally known as the “Death Star.” Footage from Star Wars: Return of the Jedi (1983) was used for demonstrations.

Lucasfilm had partnered with manufacturer Convergence Corporation to build EditDroids as commercial products. Although the system was ground-breaking, the business struggled. In some ways, EditDroid and other competitors were ahead of their time. Systems were expensive and often had to be leased. Some traditional editors were wary of the new technology. The ability to store large amounts of high-quality footage needed improvement. Nonetheless, clients started using the EditDroid, especially for television, and George Lucas used it to make The Adventures of Young Indiana Jones.

Arriving during a time of transition in filmmaking, the EditDroid helped popularize non-linear editing tools. The allure of George Lucas and Star Wars introduced people to the technology and its ability to make editing faster, and eventually, cheaper. The flexibility of the EditDroid and similar tools gave filmmakers more creative freedom.

“We needed to put film in the hands of the people as a democratization of the medium,” Lucasfilm team member Rob Lay would later tell historian Michael Rubin. “We needed to make editing systems that the people could use to write like a pen, make a word processor for video.”

By 1993, Lucasfilm was ready to leave the hardware business, and sold its creations to Avid Technology, then developing its own computer editors. By the end of the decade, leading directors were using Avid and similar programs to edit high-budget blockbusters, and consumer-level software was becoming available on personal computers, allowing anyone to edit digitally-captured footage.

—

Lucas O. Seastrom is a writer and historian at Lucasfilm.