Lucasfilm Originals: The ILM Dykstraflex

At ILM, Some Innovations Endure Across Decades

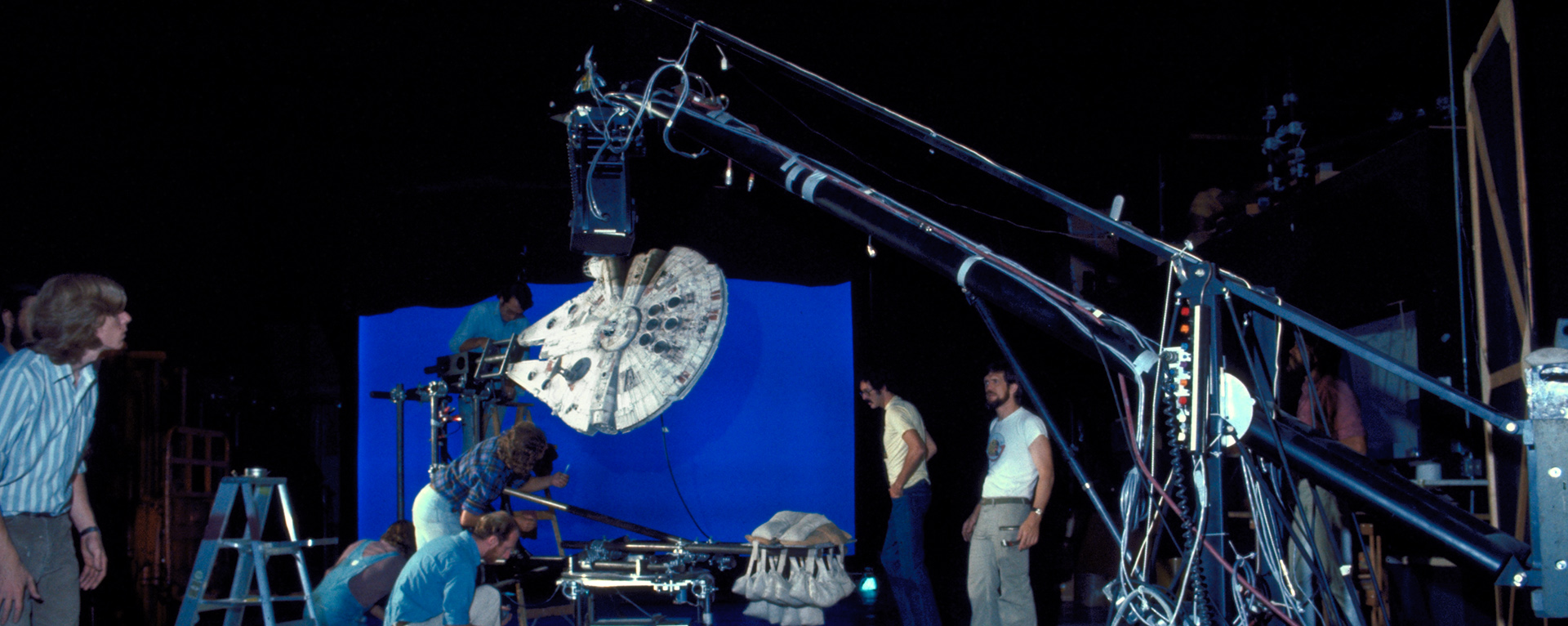

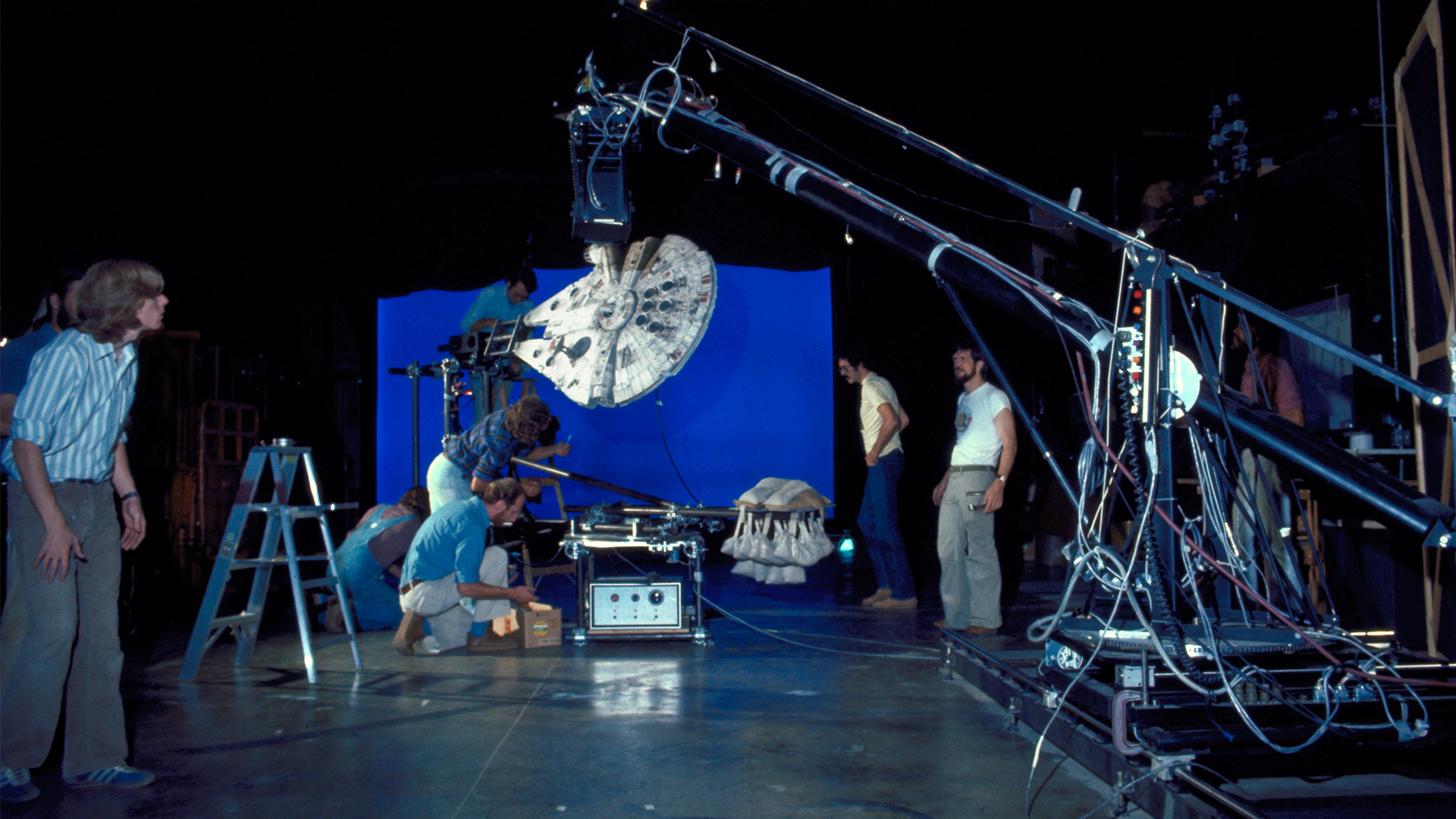

When George Lucas organized Industrial Light & Magic (ILM) in 1975 to create the visual effects for his new film, Star Wars: A New Hope (1977), one of his specific goals was to realize dynamic shots of moving spacecraft. The idea for capturing detailed model ships with aerial cinematography required a new camera system designed and built under the supervision of ILM’s visual effects supervisor, John Dykstra.

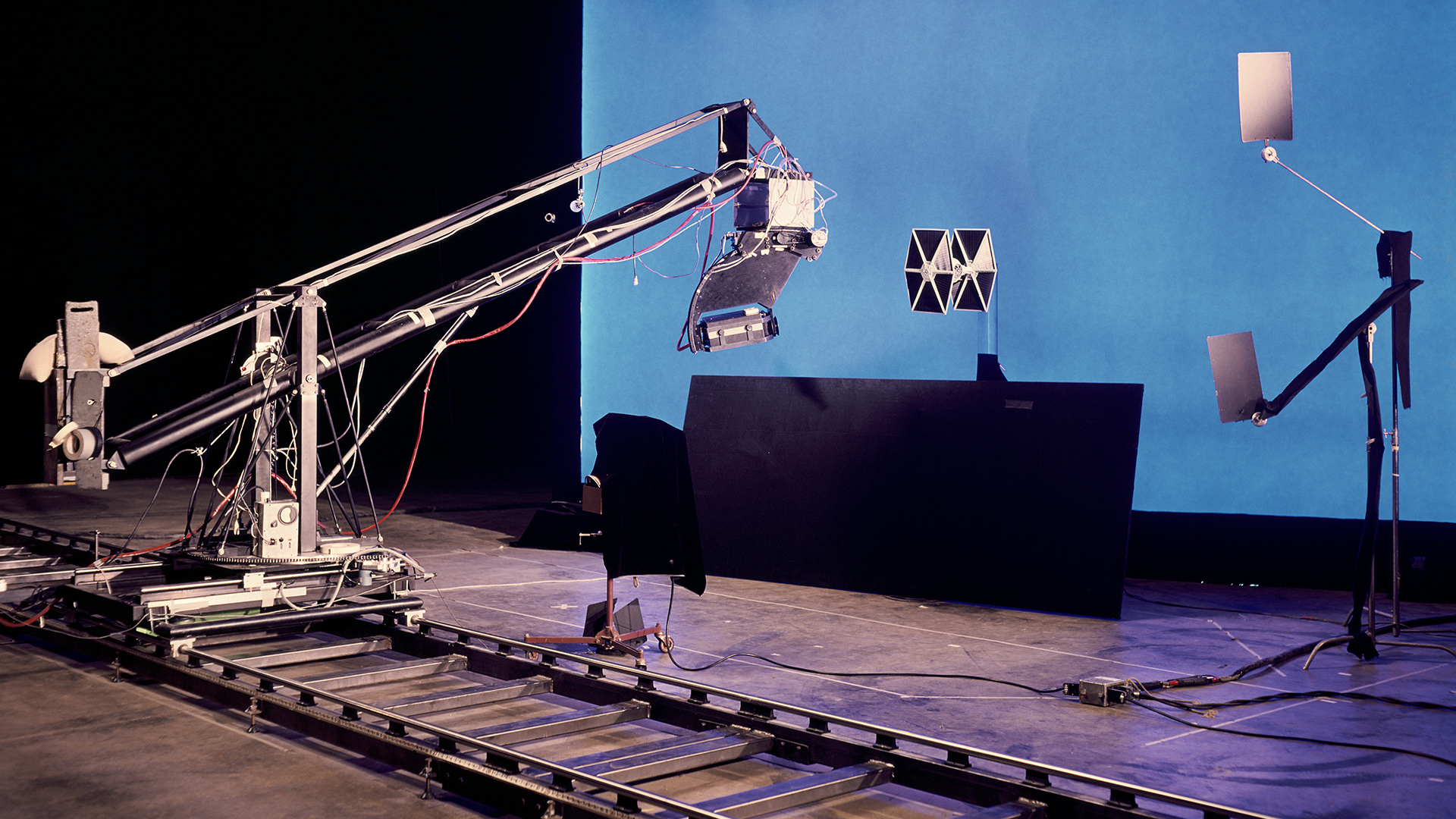

Multiple layers of a given shot had to be separately photographed. One layer might depict an X-wing fighter, another the surface of the Death Star, and still more for the starfield and blaster fire. The layers would then be combined through the process of optical compositing to create the final shot seen in the movie. Traditionally, visual effects shots were locked off in a single position so that these layers would seamlessly align together. But with the camera in motion, how would the ILM crew capture each layer to accurately match the other?

For Star Wars, George Lucas wanted the camera to swing across the action like the authentic World War II documentaries that had inspired him. The solution was a technique called motion-control. Using a mechanical system operated by a computer to move on a path specified to the fraction of an inch, a motion-control camera was able to shoot duplicate passes one after the other. The resulting elements of footage could then be accurately composited together.

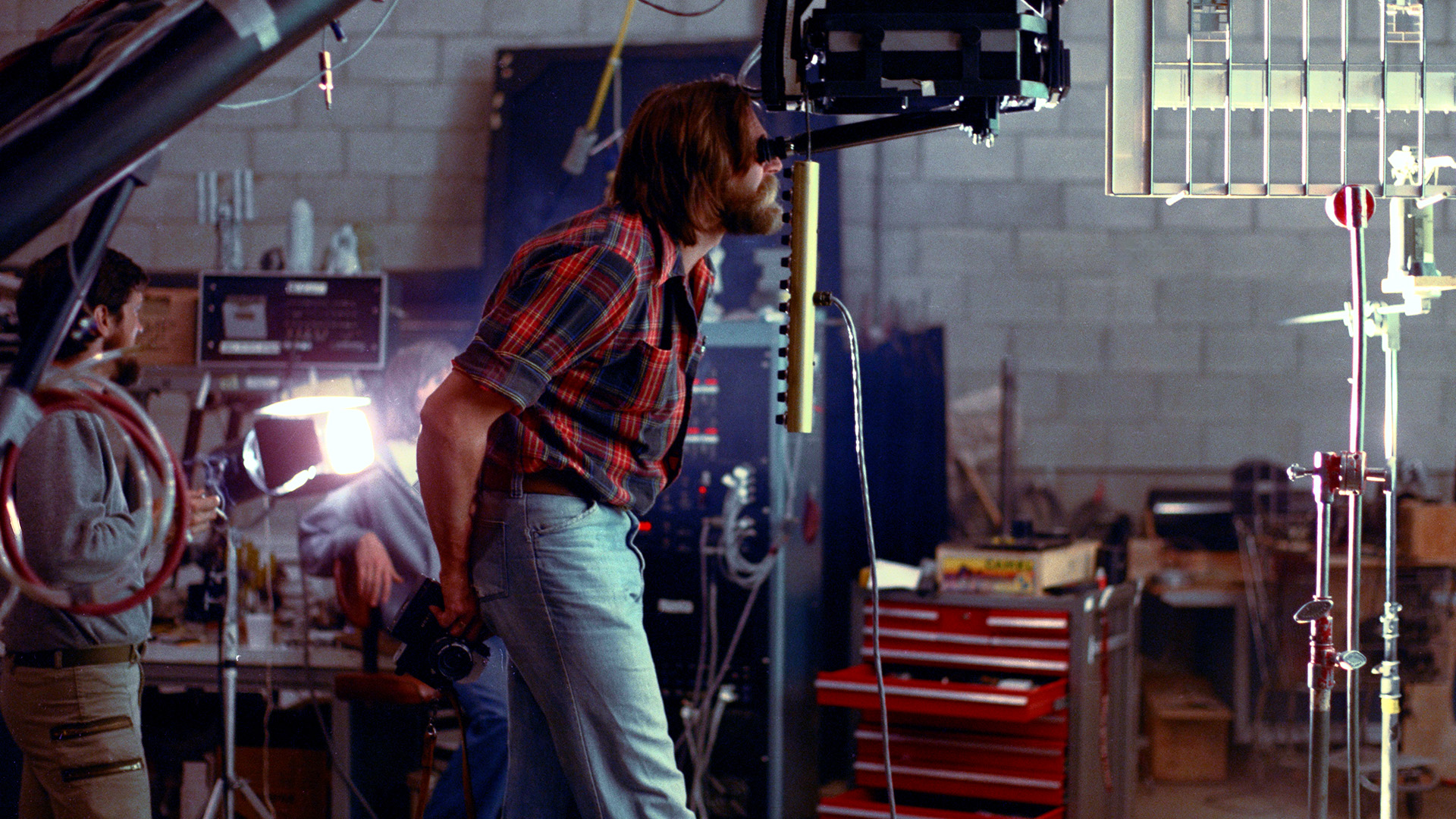

At a time when the personal computer was still years away, the ILM crew hand-built custom hardware to operate their own original system which came to be known as the “Dykstraflex.” The flexible precision of the camera was a boon for the aerial dogfights and breathtaking fly-bys depicted in Star Wars. The tool was a major contributor to the energy and vitality that so excited audiences upon its release in 1977.

The success of the Dykstraflex helped fuel the expansion of ILM in subsequent years. Their growing list of clients were attracted to the company in large part thanks to its ability to innovate new ways of creating visuals. The Dykstraflex and subsequent motion-control systems designed by the team continued to be used at ILM for 30 years before its relocation to Letterman Digital Arts Center and transition to an almost entirely digital toolset.

But good ideas don’t go away, and when filmmaker Jon Favreau became interested in reviving traditional model cinematography for the new Lucasfilm series, The Mandalorian, ILM visual effects supervisor John Knoll (who worked as a motion control camera operator during his early years with the company) decided to revive ILM’s heralded technique.

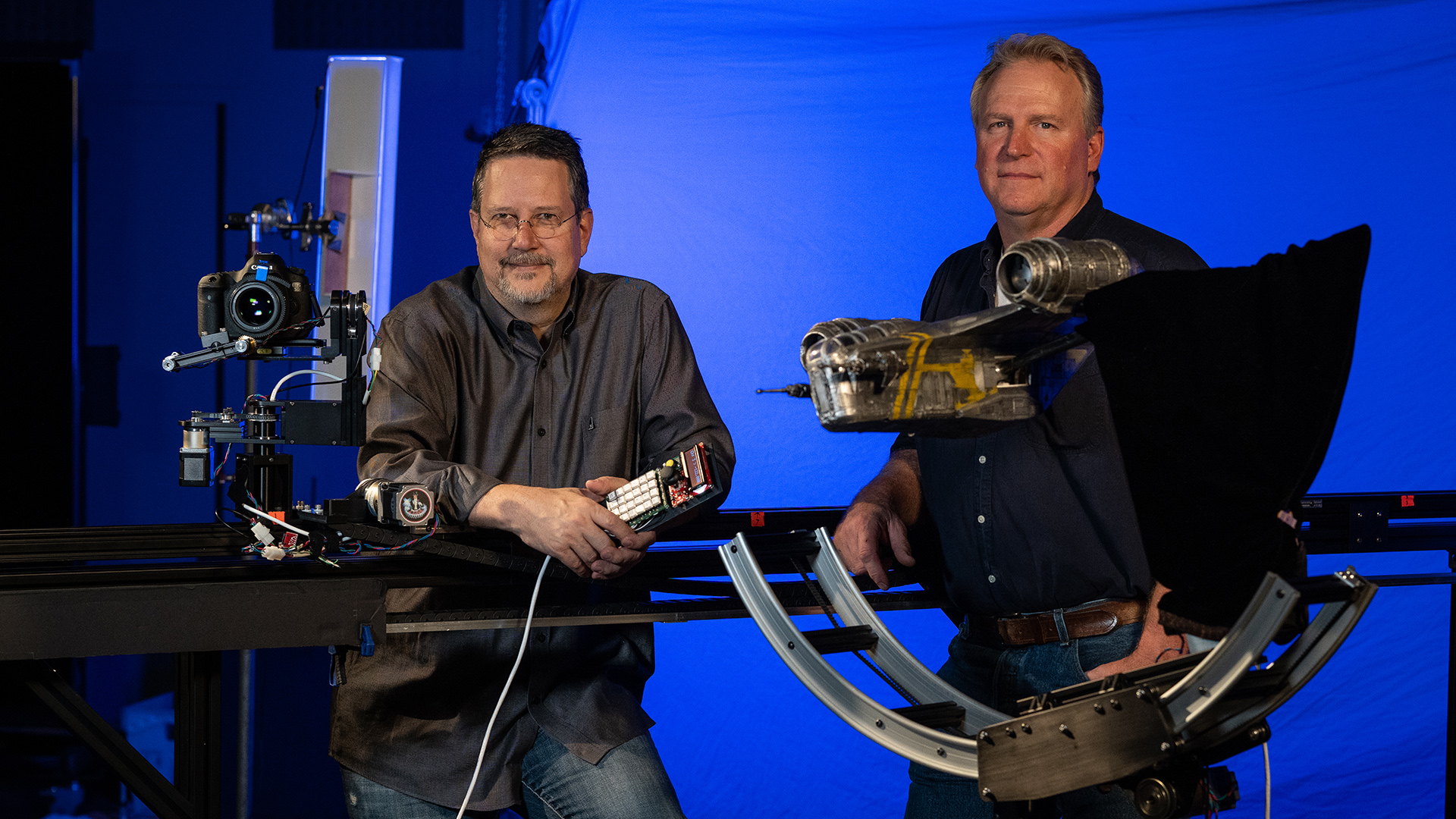

Building a new motion-control camera rig and model mover in his home workshop, Knoll was able to equip a modern digital camera to the system. Its smaller scale compared to the Dykstraflex allowed greater flexibility for its use at ILM’s San Francisco studio. The design and asset crews then partnered with John Goodson, a former member of the ILM model shop, to construct a scale model of the Razor Crest from the new series.

Motion-control cinematography has endured as a defining innovation at ILM for nearly 50 years, and continues to be used in adapted forms to this day.

—

Lucas O. Seastrom is a writer and historian at Lucasfilm.