Employee Spotlight: Daniel Cavey

The Senior Producer Talks Film School, ILM, and Star Wars Animation

To start, can you tell us your role and describe your day-to-day responsibilities?

I’m a senior producer on Lucasfilm’s Franchise Production team. We cover both franchise animation and non-fiction content. Specifically, the LEGO Star Wars portfolio is my primary role. I’m really proud of the three specials that we’ve done in collaboration with Atomic Cartoons, Skywalker Sound, writer David Shayne, and our Lucasfilm leadership team including Josh Rimes, James Waugh, and Jacqui Lopez.

As the company develops its overall strategy, we brainstorm what stories can be developed for LEGO Star Wars. Once we’ve settled on an idea, that’s my trigger to initiate the production. They give us the best release window, which sets the parameters for what the plan could be. I lay out a schedule and put together a budget with our finance team. We then take that back to our leadership and explain how we need these blocks of time and budget in order to achieve the goal. From there, we build the team of partners.

So putting this plan together is a core element of your role?

Yes, once a show is greenlit and starts development, all the creative, technical, and logistical choices arise over the course of production, and you refer back to the plan. It lets you know what you might be compromising if you make a certain decision. What are its consequences? It’s my job to communicate that to make sure everything aligns with where we want to be.

You’re sort of laying out the tracks in front of the train and preparing for changes in the route along the way.

Yes, we have something that we call the “waterfall schedule.” It’s like a primitive version of the game Tetris! It’s a graphic representation of this big plan. It’s a little harder today as we work from home, but before the pandemic, I’d print out this large schedule on the wall. Different colors and shapes track different pieces of the puzzle. You can see how everything relates to each other, and when changes come, it’s like playing Tetris and fitting things back together.

Were you always passionate about getting into movies?

I’ve always had that passion, and also for storytelling in general. I was born in New Jersey, but when I was five, we moved to England and I went to a boarding school. We had a TV there and we watched older films like the Keystone Cops or Harold Lloyd, as well BBC and nature documentaries. Then I’d come home and my parents would show me American TV shows and movies like the original Star Wars trilogy.

And how did you start working in the field?

It was the early 1990s, and I was one of those punk rock kids who was a little bit lost, and not sure what I wanted to do. A friend of mine had a dad who was an art director, and he encouraged me to try film school. I joined the film program at Loyola Marymount University. The wheels started turning.

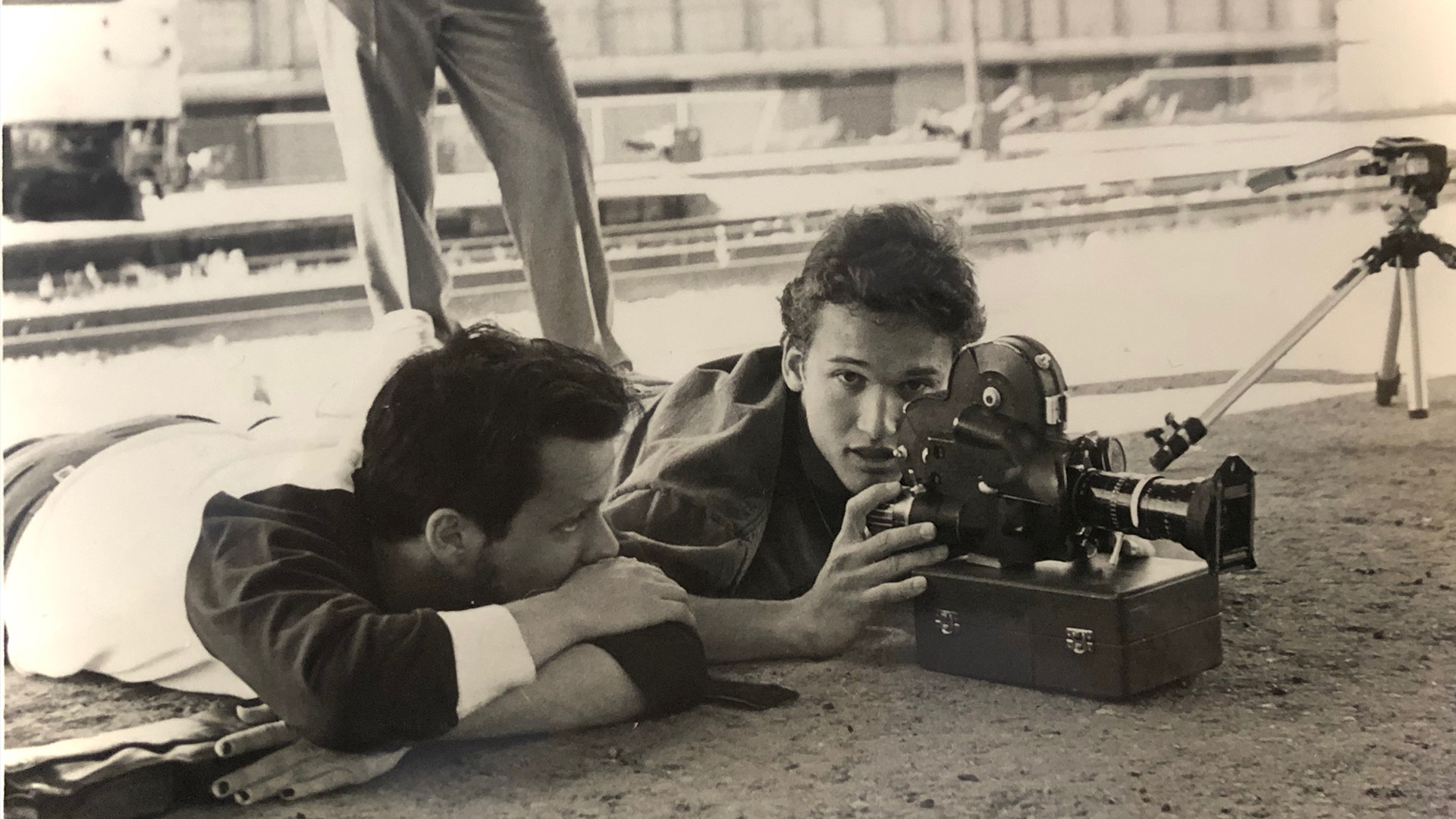

I took a cinematography course with Bill McDonald, who is now the dean of UCLA’s cinematography program. His class was a turning point for me. I did fairly poorly at the beginning. It was a big learning curve, but I was determined to be successful and make cinematography my thing. I read the A.S.C. manual cover to cover and tried to become the best camera technician I could be.

So, before you worked in production, you started your career as a camera operator.

Yes, I spent about a decade working on independent narratives and documentaries. Early on, my girlfriend (who is now my wife) was moving to San Francisco, so I moved there as well. It was a lot harder to find work, so I found a job as a rental technician and built up a network. I began working on short films, sketch comedy shows, and DJ battles. That opened me up to multi-camera work at live events, including live projections. I learned to embrace the available technology to create the image we needed. I then worked on an HBO documentary about kids running for student government called The Third Monday in October as well as a documentary called The Bridge.

During this time working around San Francisco, did you become acquainted with people at Lucasfilm and Industrial Light & Magic (ILM)?

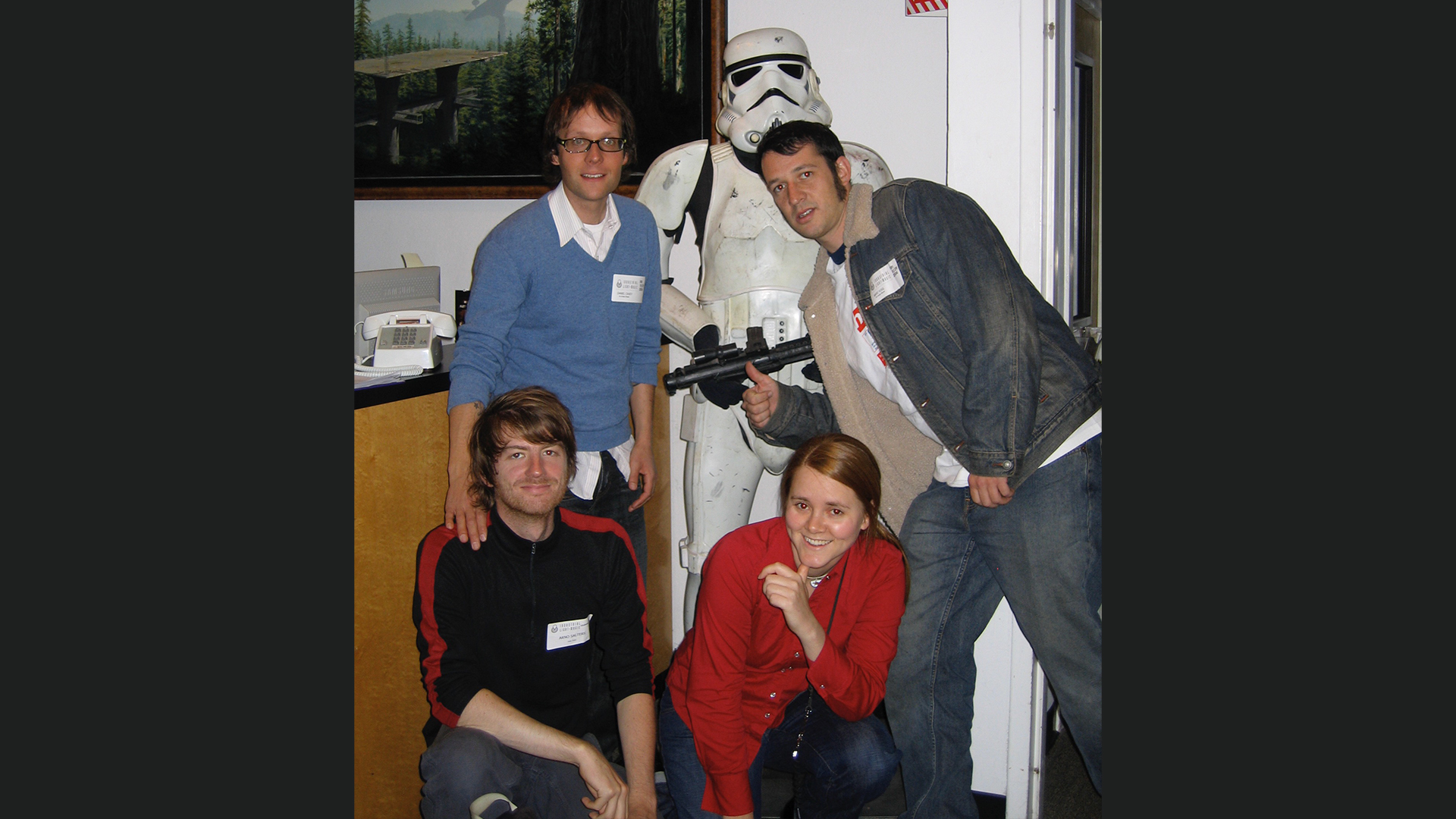

I did. Back then there was no YouTube and it was harder to get your movies in front of an audience. A group of us started a film festival called the Hi/Lo Film Festival, which stood for “High Concept, Low Budget.” There was a lot of effort to reach out to film schools and give young filmmakers a chance to get their short films screened. Around 2004, we got to do a lunchtime screening program at ILM’s old facility at Kerner. We thought it was hysterical that our festival’s tagline was “$50 million can kill a good idea.” We felt like outsiders at ILM!

And you applied for ILM around this time?

I’d first applied to be a production assistant back in 1999, and received the polite “thanks, but no thanks.” But a lot of that time when I was working on independent productions and helping run a festival was really educational. Low budget filmmaking is full of compromises. You have to work with what you’ve got. Those were the building blocks of my entry into production at ILM and Lucasfilm. I became interested in every facet of the production process.

Around early 2006, I decided to apply again at ILM as a production assistant. I had the very good fortune to have a friend and collaborator who worked at the company and gave me a referral. I felt I had better experience at that point. I was hired and assigned to work on the Windward Stage at Kerner. Lucasfilm and most of ILM had already relocated to Letterman Digital Arts Center, but some people in the model shop and the stage crew stayed behind. I did everything from helping with time cards, getting meals, watching equipment, and operating the house lights. I finally had my foot in the door! I worked on movies like Mission Impossible III and Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man’s Chest. All the people around me had the same passion that I had. It’s been said many times, but the people are the real magic of the company.

It’s fascinating that you had this opportunity to work at ILM shooting practical effects with real models on a stage.

Film school turned out to be pretty handy, because one of my assignments was to pick up the previous day’s film and load it up on a flatbed editor so they could confirm if the footage was usable. I’d first worked on a flatbed back when I was a student!

As you moved to Letterman and transitioned to CG visual effects, did you take any lessons with you?

I had already been very familiar with physical production, but ILM was a much larger scale. That probably helped me get started at Kerner. When I came to Letterman to work on Eragon, I remember producer Janet Lewin telling me that I would have to learn the new processes like composting and bluescreens. At the time, I felt I knew a bit already because my friends and I were making a stop-motion music video with basic greenscreens. But once I arrived, I remember standing in the back of the room during dailies and thinking that I knew nothing. It was the start of a whole new learning process. It could’ve been overwhelming, but I tried to just do my best to learn everything.

As someone with a fair amount of general filmmaking experience, there was still quite a bit to learn about the specifics of ILM and visual effects.

In a production role, you don’t need to be able to do every task that the artists do, but you need to understand what’s involved. In order to interact with the artists in a respectful way, you should know what might be a big note or a small note. That translates to the bidding process and how ILM communicates with its clients. Now that I work on that client side with Lucasfilm, it’s invaluable to understand what’s achievable and what might be harder to accomplish.

One of the more unusual ILM productions that you worked on was the animated feature, Rango. Could you discuss your involvement on this film?

After working on many different projects, I’d had the opportunity to become a plate coordinator on Iron Man 2. I spent a few months onset helping with the motion-capture effects. As Rango became ready for production, I was pulled off Iron Man to become associate production manager. In the past, I’d worked on ILM shows in the range of 100 to 400 shots. Rango had some 1,500 total shots. It was very intimidating. I realized that the techniques I was using to track the work needed to be more systematized so it was scalable. Whereas before with a smaller crew, I could check in with my intimate group of artists every day, on Rango we had dozens of people between San Francisco and Singapore.

How does one begin to plan for such a large shot count?

Carol Norton was the production manager. She had come from the Dreamworks feature animation department to work on Rango. Carol showed me how to look at the overall scope of work and break it down into a sequence-based plan. Looking at the whole film is too overwhelming. You break everything down to understand how many people and how much time is required for a certain task. Carol taught me how to look at the bigger picture using broad strokes and then flesh out a plan.

And you’re creating this plan with the coordinators and other folks on the production team?

Yes, it’s really important to have good communication so that everyone has the details that they need. Once everything is broken down, we have to think about casting the artists to the assignments. It’s kind of like food pairing (I love food analogies!), because you try to determine what goes well together. I collaborated with the animation supervisors Hal Hickel and Kevin Martel to decide which shots were the best for specific animators. Some were better with action or others with emotions. It was really great when animators would come and ask to work on different sequences so we could help them find that satisfaction in their work. It all stems from what Carol taught us. There were long hours, and in the final weeks, the animators were helping pick up each other’s work to get things finished. The camaraderie was really amazing.

And then you had the chance to work with Carol Norton on the ILM theme park crew, correct?

Yes, they were getting started on the Soarin’ Over the World attraction for the Disney Parks and Pirates of the Caribbean: Battle for the Sunken Treasure at Shanghai Disneyland. It was really special to collaborate with the group at Walt Disney Imagineering (WDI). In terms of the challenges, it was sort of the opposite of Rango. Instead of scalable volume with large batches of shots, with Soarin’ we had this unique camera rig with five red cameras made by WDI, and we had to render a 5K image at 60 frames per second. This was back in 2013, and that’s a lot of processing!

We’d go down to a WDI facility where they had a scale version of the projection screen mocked up for review. And whereas on a show like Rango we’d all cram into a screening room and review dailies, for this project each of us had to climb up a ladder to a viewing station and look through a window! It was another great learning experience. WDI was just as passionate about the details and fidelity of the image as the artists at ILM. It’s this great blend of technology and storytelling. And because it’s a theme park ride, these are seen multiple times over many years.

What was the experience like coming to the Lucasfilm franchise team?

I’d always volunteer at our Lucasfilm Trivia Night event for employees. In 2018, I was working as a server and I bumped into Lucasfilm’s vice president from franchise production, Jacqui Lopez. At ILM your work is often project-based and it wasn’t clear where I’d be going next, so I was interested in other opportunities at the company. Jacqui presented me with this great chance to work on a new Star Wars project for kids called Galaxy of Adventures. It was a short-form animated web series all about helping inspire kids about moments in the saga.

A lot of artistry and care went into them. I worked closely with two other executives James Waugh and Josh Rimes to develop the themes we’d focus on. Before, I was mostly concerned with technical requirements, and it was a delight to be involved with questions of story. Titmouse was the animation studio and they worked in an anime style. They described the series as “the way you remember a scene from Star Wars, but how you play it out with your toys.” It always has a little more zap to it! It was another learning lesson in a new format.

It’s fascinating to hear how you’ve continuously reinvented yourself and been willing to learn and apply your skills in new ways.

Every project is a learning experience. As a team, we want to take all the best things that we learned and keep building on them into the next project. I’m grateful to have had the chances to move between these different parts of ILM and Lucasfilm. From the stage and model shop at Kerner to the CG department to motion-capture onset to where I am today, it’s been a great experience to be exposed to all these parts of the process. That all serves what I do at Lucasfilm today.

Watch dear xxx, Cavey’s student film from Loyola Marymount University.

Lucas O. Seastrom is a writer and historian at Lucasfilm.