The Digital Road to The Phantom Menace: ILM Artist Jean Bolte Talks Viewpaint

An innovative paint tool first created for Jurassic Park lent new detail and richness to ILM’s animated characters.

“The Digital Road to The Phantom Menace” is a Lucasfilm.com series that explores Industrial Light & Magic’s work in pioneering digital visual effects, and specifically how advancements on projects throughout the 1990s became essential tools for creating Star Wars: The Phantom Menace. The most ambitious visual effects project ever undertaken up to that time, the film is now celebrating its 25th anniversary.

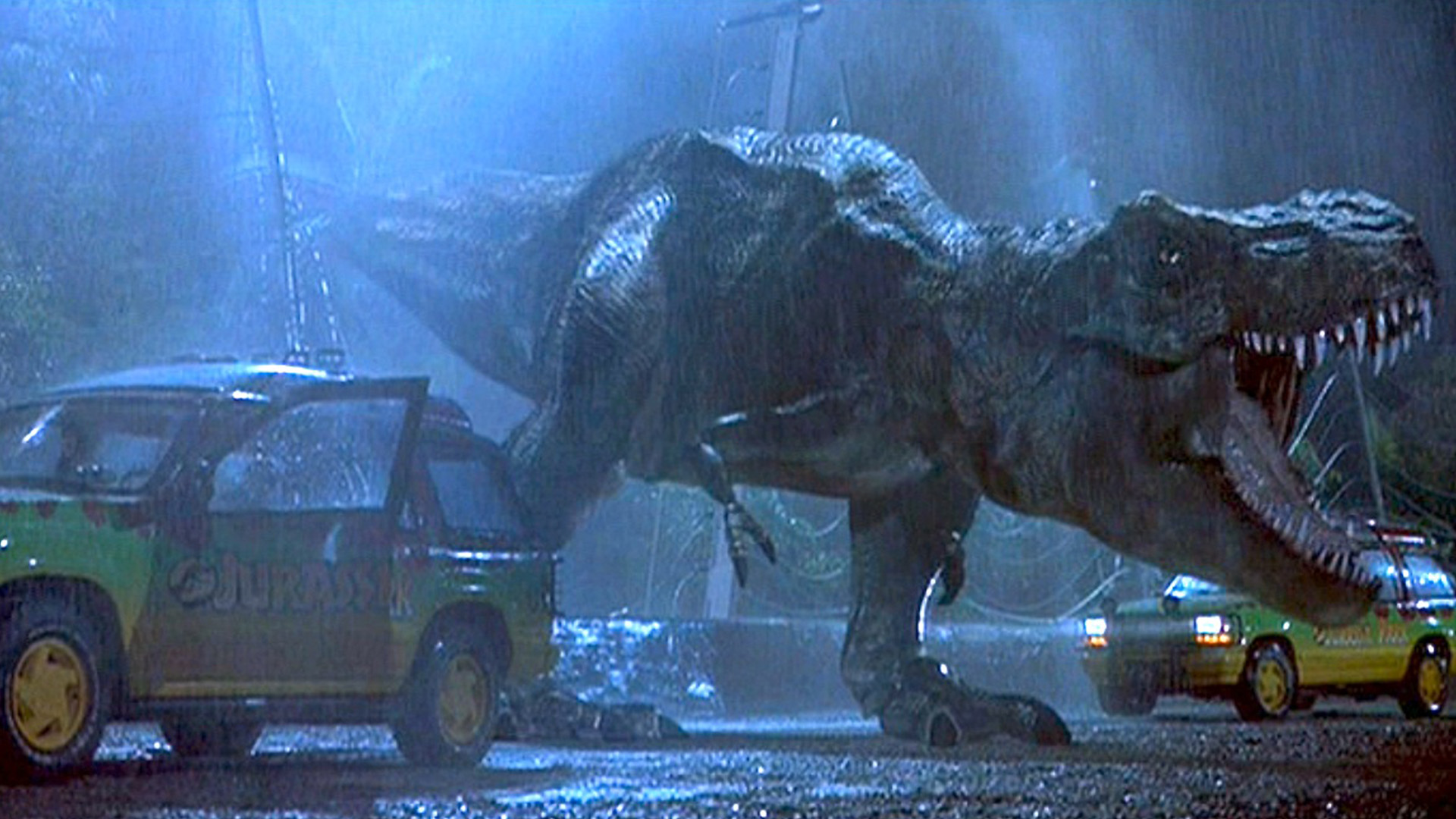

The release of Jurassic Park (1993) with its breathtaking depictions of computer graphics dinosaurs had signaled a renaissance in visual effects. It wasn’t the first movie of its kind, however. The artists and technicians at Industrial Light & Magic (ILM) had been innovating digital techniques for many years on projects like The Abyss (1989) and Terminator 2: Judgement Day (1991). But one of the key breakthroughs in the creation of Jurassic’s creatures was the depiction of their natural skin textures, something that up to that time was largely unfeasible with existing tools.

Jurassic’s co-visual effects supervisor Mark Dippé would tell Cinefex magazine that “we just didn’t know how well we’d be able to nail down the skin and features. There were a lot of problems involved in creating photorealistic dinosaur skin. How do we get light to react with it so that it has the right kind of sheen? How do we get the light to react to all the bumps on the skin? How do we create those bumps? We couldn’t model all the detail because the skin was so complex. It would just be an impossible job. All of those problems had to be solved.”

ILM’s answer was to create new software that allowed their artists to bring the organic qualities of these iconic dinosaurs to the screen. The implications of this new tool would influence the trajectory of many visual effects projects to come, including Star Wars: The Phantom Menace (1999).

“A story I’ve heard is that [digital technology supervisor] Tom Williams came through the Model Shop one day and saw me painting,” explains former ILM artist Jean Bolte, who at the time of Jurassic Park was working as a traditional painter and model maker. “I was working on a giant eyeball and painting the iris. Tom went back and said, okay that’s the next thing we need to work on in CG, getting paint on our models. I like the idea that I might have had some small part in helping motivate that next step without having any expertise in the technology.”

Developed by Tom Williams and John Schlag, among others, the tool that brought new visual depth and richness to Jurassic’s dinosaurs was called Viewpaint. Its chief aim was to allow the digital artist to more easily paint skin and textures onto a three-dimensional surface. “Traditionally in CG, the artist had to paint the flat surface and assimilate what it would look like wrapped on the 3D object,” artist TyRuben Ellingson would explain in the book, Industrial Light & Magic: Into the Digital Realm. “Viewpaint allows you to see maps on the geometry of the sculpture as you paint.”

The software helped bring to life the running herds of gallimimus and the hulking Tyrannosaurus Rex stomping her way through a stormy jungle. As Bolte explains, “Viewpaint took some of the ‘CG-ness’ out of things. There was so much perfection and smoothness at that time, and all of a sudden there was a way to hack away at things and have them tell a story. Just by being on a screen, there was a story there. You could tell how old something was. If it was a creature, was it a predator or prey, or aquatic? How did it live? Was it old and beat up? And it’s not just creatures, but hard-surface as well. Is it rusty or scraped in some way? Those things tell stories too.”

In the wake of Jurassic Park, Bolte would be among ILM’s first Viewpaint artists. Both she and fellow model maker Susan Ross would train with Carolyn Rendu, who had painted most of Jurassic’s dinosaurs. “Carolyn was the first to do it, and she pioneered all of that,” says Bolte. “It took a long time in those days to paint a dinosaur, five or six months. Carolyn was a trained artist. She was very capable at trying her hand with something so new and solving the problems. She was very patient and would work through everything with me. She had a strong art background, a kind of European flair, and she loved art history. We shared that, and I learned a lot from her.”

Although Viewpaint was an important step forward, it was still very much a computer-based tool. Working in close collaboration with the CG modelers and shaders, the painters arranged their data along mathematical coordinates that determined points of color. “The first steps in Viewpaint involved a lot of tedious drawing and diagrams to make sure that you had it laid out,” says Bolte. “Once you finished with the color pass, you’d close down your system, open it up again, and apply the bump map. For something like the elephant in Jumanji [1995], this would include all of the animal’s wrinkles. There wasn’t an easy way to take the information from the color map and transfer it into the bump map. That was another big leap to make sure those two married up.

“We take it for granted now that, as you work, you can see the paintwork appearing on the form with adjustable lighting,” Bolte continues. “Everything was flat when you painted back then, with flat shading. I found the separation to be fascinating but also frustrating, because in the Model Shop the material would give something back to you. If you picked up a tool with teeth in it and ran it over clay, squirted paint on it, and spritzed it with alcohol, you’d get all this stuff right in front of you. Instead, with CG, everything was so blind from one step to the next. It was a real triumph when you put it all together and it actually looked like the form you had in your mind or in the concept artwork. It wouldn’t come together until you really hashed it out.”

All the same, Bolte found that she could adapt to it fairly well. “I loved painting on the computer,” she says. “What surprised me is how quickly my brain made the connection to what I was doing on a screen as opposed to what I might be doing on an object. Every time there’s been an upgrade in something like Viewpaint, it’s been about getting us back to that experience of standing in front of something and making it by hand with simple tools. These things were written into the programs.”

Throughout the 1990s, Viewpaint remained an essential tool for ILM’s growing number of digital creations of every kind (Bolte’s first official paint assignments were Twinkie and Hostess cupcake models for 1995’s Casper). At decade’s end, The Phantom Menace would be ILM’s most ambitious project to date. The first movie to include more than 2,000 visual effects shots, the Lucasfilm production required hundreds of both organic and hard surface models. As Bolte recalls, the Viewpaint team numbered some ten artists, as many as they could accommodate, in order to create everything on time.

Bolte herself kept one foot in the practical world, often returning to the Model Shop to help create the physical maquettes for major characters, something unique for the time. These sculptures were then used as important reference tools by the digital artists. Across this work in both traditional art and computer graphics, the bulk of the major characters were created over several months. “But for the minor characters,” as Bolte explains, “George Lucas had a very sharp sense of how much time and budget he wanted to spend on any of the background or supporting characters.

“Normally, we’d knock out something and show a rough version as a first pass,” Bolte continues. “But I quickly discovered that George was approving these versions. So I had to tell the team to hold onto their characters a little longer and keep working it up, because you may get it taken away from you. We’d always try to sneak details in after they’d been approved! We wanted to keep improving things, but for the production team, once George said it was good, it was onto the next thing.

“I think George knew the entire film in his mind before anything went into the camera,” says Bolte. “So it was possible for him to say that a model was good enough because he knew we wouldn’t see the back of it, for example. Having a director like that is a kind of luxury. So often, you’ll be in a situation where you’re working on something and all of a sudden you find out that the finger is in close-up, which you hadn’t planned for, but the director changed everything around in the scene. George knew when it was enough and how things would be used, and he stuck to it.”

In the decades since projects like The Phantom Menace and Jurassic Park, ILM has continued to push the capabilities of visual effects, with ever-increasing quality in photorealistic texture and detail. Although the advances of recent years can leave earlier creations feeling less refined, Bolte insists that their past work holds up remarkably well. That’s thanks in large part, as she explains, to the animation.

“The animation is crucial to the audience believing something,” Bolte says. “A simpler model and paint job can actually make room for the audience to step forward and say, ‘Yes, I’m with you.’ If you think about E.T., who everybody loved, what if he had been intensely-detailed like we are capable of doing today? I think something would’ve been lost. George seemed to have an innate understanding of that on The Phantom Menace.

“When you look at it, the hard surface models hold up beautifully, and the creatures hold up in the sense that they all relate to the world they exist in,” Bolte continues. “In no way are they examples of the peak of our capacity for detail. If you look at what we can do now and compare, it’s easy to be very critical. But something from recent years like Grogu in The Mandalorian [2019] is a perfect example of how everyone understood that the technology was there to do it, but that there’s a charm to something with simplicity. It gives the audience something to do.

“So when you look at The Phantom Menace creatures and see that they’re not nearly as photoreal as we might wish they were, it gives the audience a way to enter the movie and say, ‘I can relate to this,’ especially for kids. You’re an active participant in caring about these creatures. If everything is so detailed and the camera can fly right into the eye, it can cause you to sit back and not be so engaged in what you’re seeing. I’m not saying we shouldn’t be pursuing everything we are in CG, especially with humans. To keep making strides is important, but I also think there’s a reason why Grogu was so popular. In the case of that character, and others like him in The Phantom Menace, there was a reason not to be hyper-detailed.”

Each film has its own specific palette and tone, and it’s the task of ILM’s artists to realize their visual effects in a way that is consistent with the filmmaker’s vision. “The one thing you can never lose is the quality of the animation,” as Bolte reasserts. Going back to the breakthroughs on projects like Jurassic Park, it was tools like Viewpaint that empowered ILM’s animators to bring these new characters to life. And as Bolte reflects, “everybody contributes to the story, and that’s something I liked about CG. I thought it was well-acknowledged. To me, it seemed that everybody’s role was important.”

Lucas O. Seastrom is a writer and historian at Lucasfilm.

—

Lucasfilm | Timeless stories. Innovative storytelling.